As an institution dedicated to documenting and sharing our town’s history, the Litchfield Historical Society is primarily a collector of stories. Sometimes, those stories come in unusual, and even unfamiliar, packages. When a regular supporter of the Society donated this ceramic and glass vessel to our museum collection, it set me on a research path that began in Litchfield, moved to the American South, and ended in Central Africa.

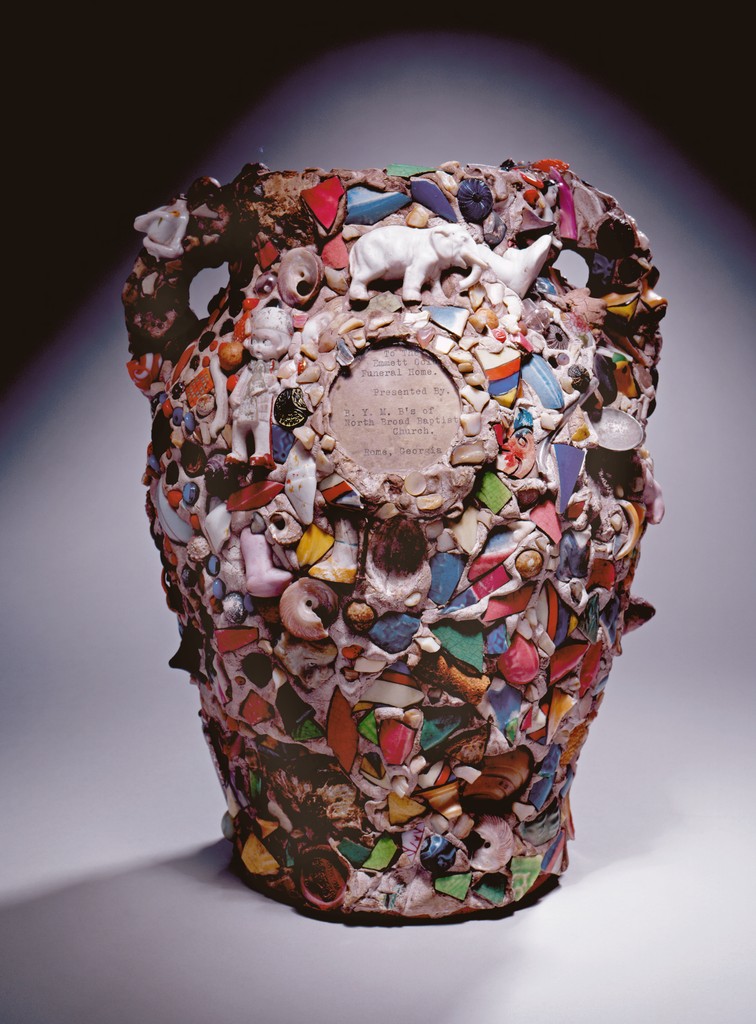

The vessel is striking in its appearance and composition, formed by covering a commercially produced glass bottle with clay or putty. Ceramic fragments were pressed into the clay while it was wet to form a mosaic of colors, patterns, and shapes. The most noticeable (and charming) feature of the mosaic is a pink, petite pig head poking out from the center of one side.

This piece is the first and only memory jug (also commonly called a memory vessel or jar) in the Litchfield Historical Society collection. Memory jugs are complicated objects, representing a craft tradition informed by African cultural and religious beliefs, imported to America by those forcibly enslaved, and later popularized through the sentimental culture of the Victorian era. This memory jug dates to the turn of the twentieth century (1890-1910) and was made in Northfield, a village in the town of Litchfield. It was likely crafted by Hattie Davida Gustafson Blakeslee (1890-1963) or her mother, Christina Nilson Gustafson (1857-1931), using ceramic fragments found in the trash pit or midden on the family farm.

Origins of American Memory Vessels

Most examinations of memory jugs as cultural objects trace their origins to Central and West Africa and the Bakongo (or Kongo) people who lived along the Atlantic coast. Bakongo burial practices include the creation of grave markers containing objects associated with the deceased, often broken into fragments. According to John-Duane Kingsley in a 2021 Decorative Arts Trust Bulletin article, the fragments serve as a “rupture point between the spirit and their attachment to the object,” allowing the spirit to be remembered and appeased while also “severing their attachment to the object and also the realm of the living.” Bakongo grave markers often utilized water jugs and other vessels, possibly a connection to the Bakongo belief that the land of the living and the spiritual realm of the ancestors were separated by a watery boundary, traditionally called the kalunga line.

As enslaved Africans forcibly moved west, African cultural traditions such as the Bakongo burial practices arrived in North America. The tradition of memory jugs was carried on largely in the South, and primarily within African American communities where they may have continued to serve as grave markers. Kingsley’s article points out that an existing Southern practice may have provided a “further foothold” for the integration of memory vessels “into American commemorative and burial objects.” Potters in the South were already creating ceramic grave markers resembling urns or other vessels, which served as “inexpensive alternatives to stone slab headstones.”

Memory jugs gained more widespread popularity in the second half of the nineteenth century, as the traditional form assimilated into the craft culture and sentimentality of the Victorian era. While still often meaningful to their makers, memory jugs of this period are more representative of a sculptural art form than a ceremonial object. The process of creating memory jugs appealed to Victorian Americans who were already taking up scrapbooking, sewing crazy quilts, and decorating frames and interiors with found, eclectic, and sentimental objects. Memory jars enjoyed a second revival in the 1950s and 1960s, especially in African American communities in the Appalachia Region and the South.

As objects offering an “intersectional appeal” described by Kingsley as “a synthesis of craft, folk history, and memorials,” it is unsurprising that memory vessels are sought after by collectors of American folk art and are preserved in the collections of museums and historical societies.

Collection Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2007-172-3.

Collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1986.65.310.

Making a Memory Jug

While all memory jugs vary in terms of incorporated materials, the general form stays consistent. Most surviving American examples are formed around a prefabricated vessel such as a ceramic jug, vase, or glass bottle. The vessel is covered in a layer of putty, cement, plaster, or clay. While the surface is still wet, various objects are pressed into the adhesive layer: ceramic and glass fragments, beads, coins, stones, buttons, shells, mirrors, toys, tools, and even photographs. Once the adhesive layer dries, the incorporated materials are secured in place and the memory vessel is complete.

Instructions for creating a memory vessel are readily available online. If you have sentimental objects saved up in a box or drawer, consider making one of your own!

Further Reading

Jennifer Priscilla Hornby, “Memory Jugs: Change and Continuity in a Traditional American Art Form” (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 31; https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/31

John-Duane Kingsley, Decorative Arts Trust Bulletin, 2021; https://decorativeartstrust.org/memory-vessels-post/