Note: This is the first of an ongoing series of articles featuring objects from our upcoming exhibit, Antiquarian to Accredited: A Look Inside the Historical Society. Check back often for new objects and articles!

First, let’s set the scene, courtesy of HBO’s miniseries John Adams. Adams, played by Paul Giamatti, has just returned to his Boston home when he hears church bells and shouting coming from the streets—sure signs that a fire has broken out. He rushes outside, carrying a leather bucket to a nearby water pump only to find the pump encased in ice. Two men struggle to push a hand tub (an early form of fire engine) down the street, calling for Adams’s help when it tips over. After righting the tub, Adams dashes through the crowded street to the next water pump. Before he can fill his bucket, the sound of a gunshot cuts through the night air.

If you have seen the series, you know what happens next. There was no fire that night, despite the ringing bells and commotion in the streets. Adams instead witnesses the aftermath of the Boston Massacre, setting the stage for his successful trial defense of the British soldiers involved (the story arc of the first episode). Setting aside any discussion of the show’s historical accuracy, it’s opening scene provides a vivid depiction of what it was like to fight fires in early America.

Our focus here is the rather plain-looking object that Adams was carrying: a leather fire bucket. The fire bucket is a wonderful example of a utilitarian object that can tell diverse stories.

Story #1 – Fighting a Fire

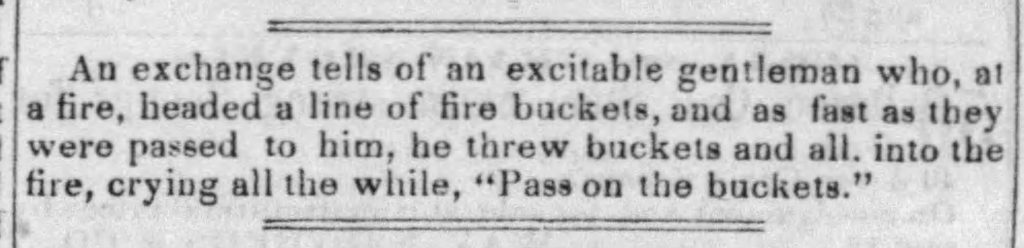

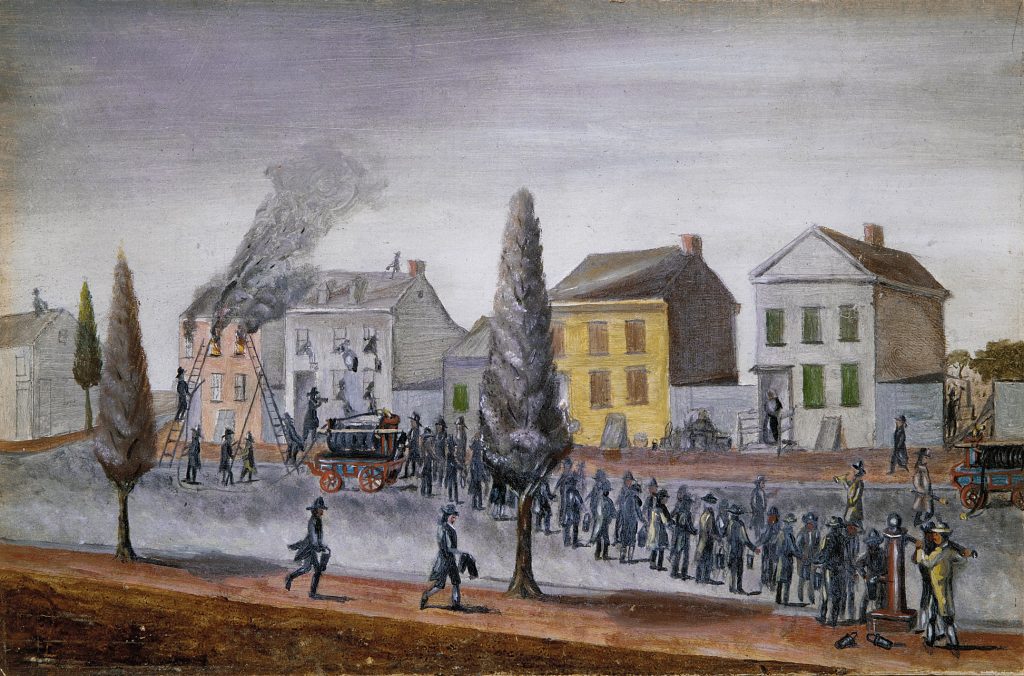

In an era before professional fire companies, fire buckets symbolized the public safety role played by members of a community. When a fire started, shouts of “Fire!” and ringing bells would call residents to action. Those who could help fight the fire would rush out with their fire buckets and other implements (ladders, fire hooks, axes, etc.). Those who could not help were still expected to do their part by tossing their fire buckets into the street for others to use. Residents and volunteer fire companies formed “bucket brigades,” chains of people passing full buckets from a town well to the burning structure and returning empty ones to be filled again.

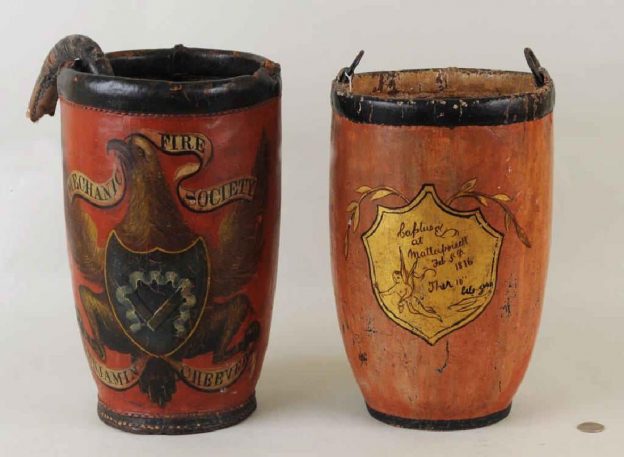

Buckets of water might not save a burning building, but they often slowed the fire enough to prevent it from spreading to nearby structures or allow the property’s owners to salvage belongings. When the fire was over, any remaining buckets would be gathered and brought to a central place where they could later be retrieved. Most fire buckets you will see from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries are made of stiff leather with painted decoration. The most basic are marked with the owner’s first initial and last name. More intricate examples have dates, stylized lettering, personal crests, and even detailed scenes and motifs. If an example is marked “No.” followed by a number, it indicates that the owner kept multiple fire buckets.

The fire bucket remained an important part of fire fighting even as fire companies grew more organized and better equipped. Rudimentary fire engines, such as the hand tub seen in John Adams, used hand pumps to direct water through a short hose and onto the burning structure. Early versions still needed to be filled with water by hand, requiring the use of a bucket brigade. As metal replaced leather, fire buckets saw continued use as an inexpensive and reliable first line of defense against smaller fires and were often stored close to where fires could start.

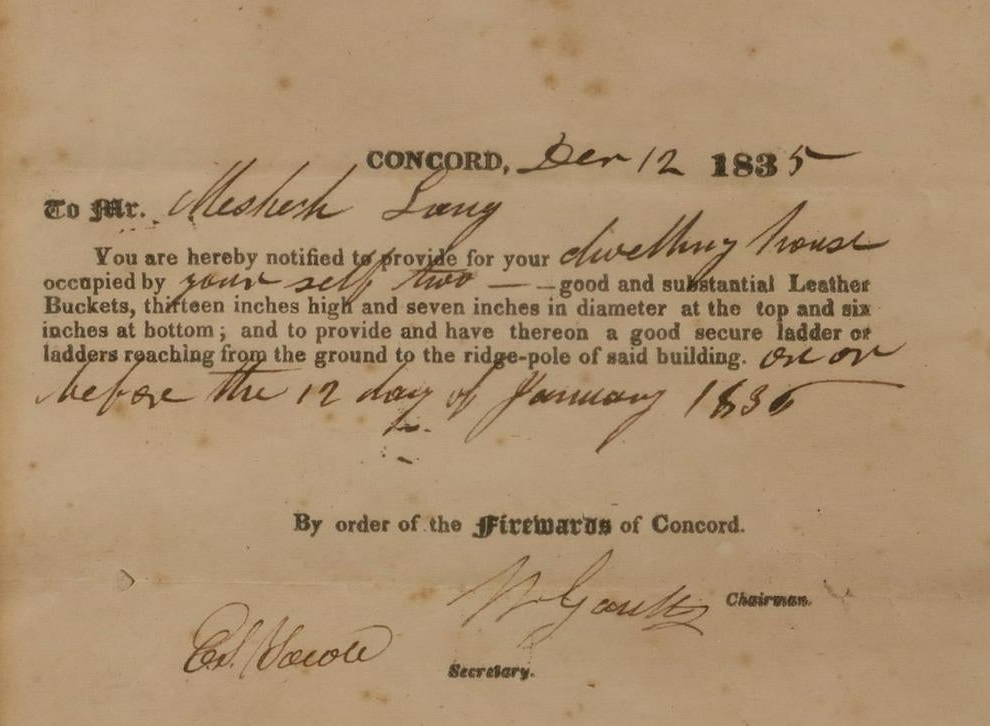

Story #2 – Town Planning

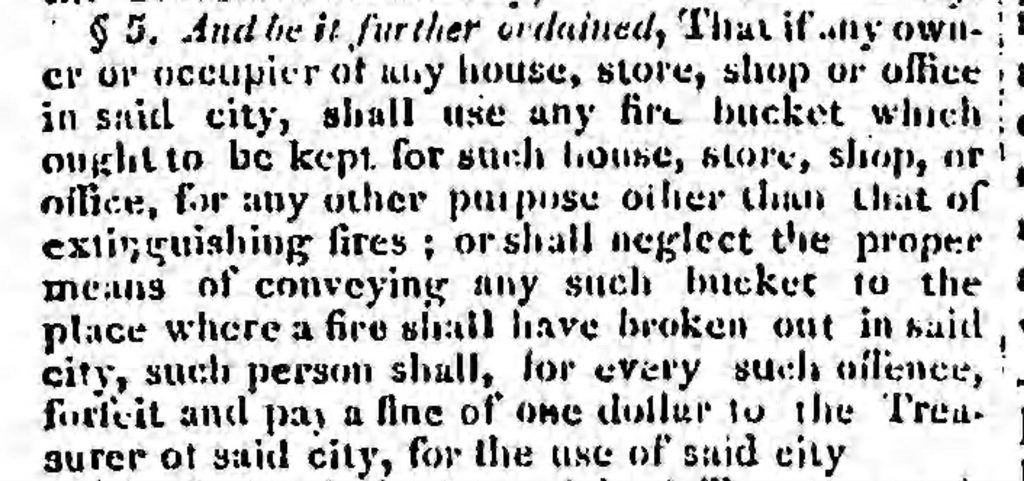

The great thing about researching fire buckets is that they frequently appear in town ordinances, newspapers, and institutional documents. Cities such as Hartford and Boston created by-laws outlining the proper number of fire buckets to be kept by residents and businesses, and levied fines against those who failed to procure them. The August 9, 1815 issue of The Connecticut Courant published a notice on the front page with an “addition to and alteration of a By-Law for preserving the Buildings in the City of Hartford from Fire.” The new by-law outlined the creation of a volunteer fire company and required every male resident aged 15 to 60 to respond to fire alarms “unless prevented by necessity.” A further paragraph set a fine of $1.00, per violation, for any person failing to convey their fire buckets to the scene of a nearby fire.

Before towns created municipal fire companies, motivated residents often organized into firefighting associations and mutual societies that sought to protect members against property damage and loss. Formed in 1764, the Mutual Society of Boston included a provision on fire buckets in the second act of their by-laws. They too listed a fine for any Society member who failed to provide their fire buckets at the sound of the alarm.

Story #3 – Art and Commerce

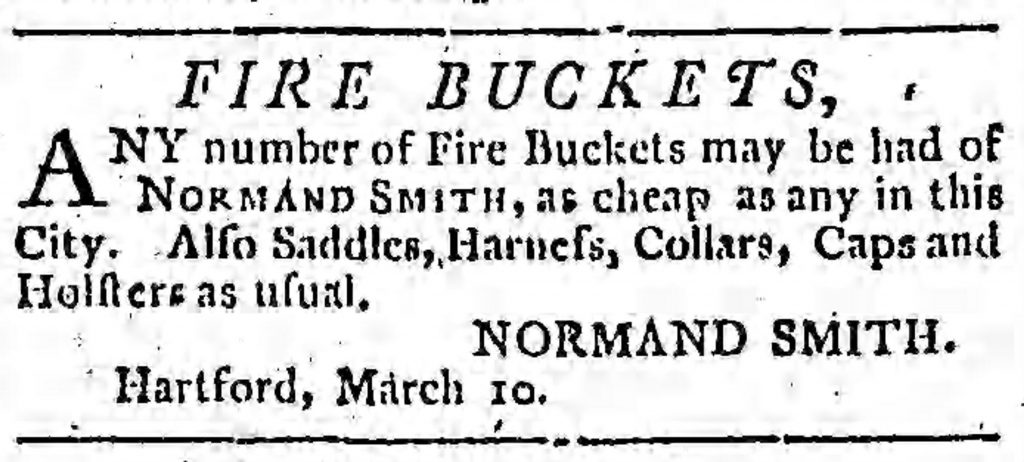

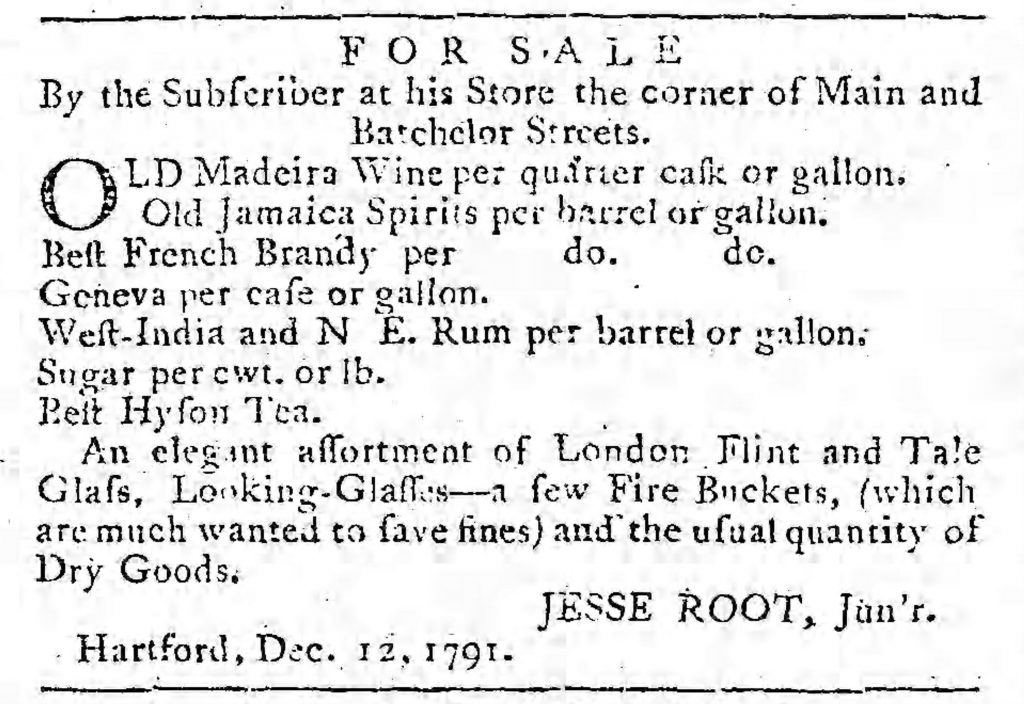

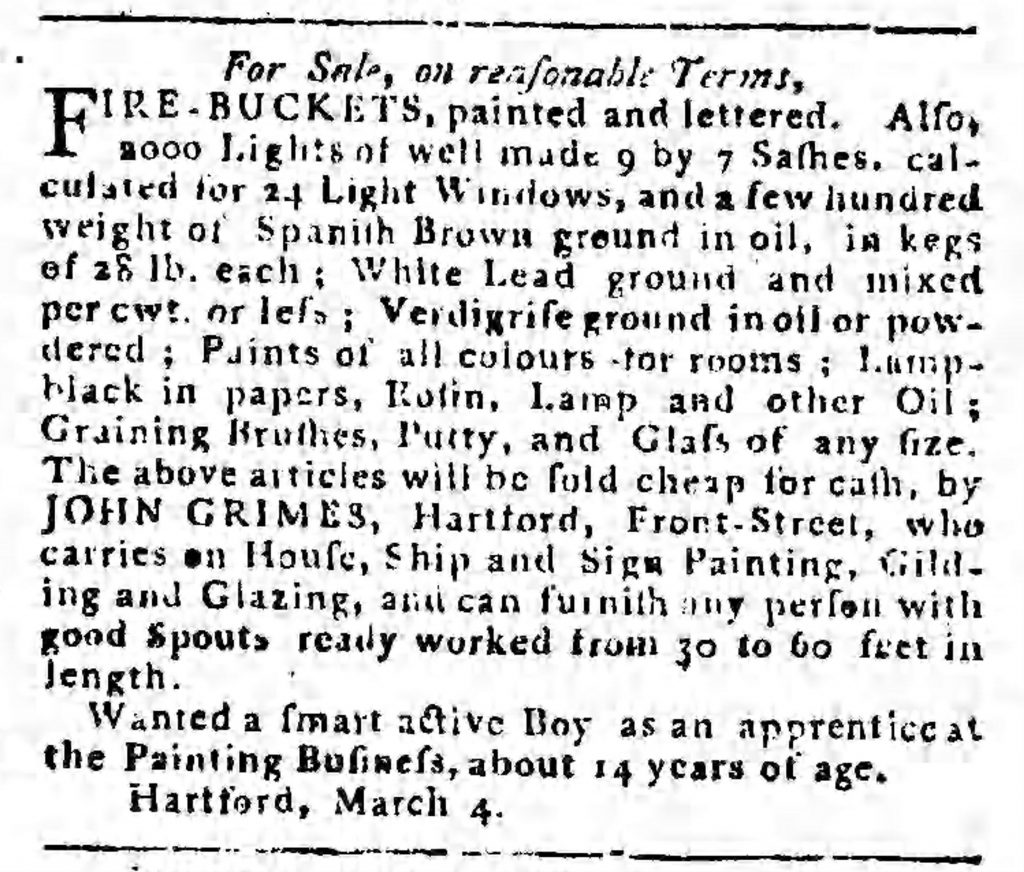

With fire buckets serving such a necessary (and often required) role in community safety, there had to be an easy way of acquiring new buckets and replacing old ones. A quick search through the advertisements in any period newspaper will likely turn up at least one merchant, leather manufacturer, or other artisan offering fire buckets for sale.

Of particular interest to us was a 1791 advertisement by Jesse Root Jr., who offered “a few Fire Buckets, (which are much wanted to save fines)” at his Hartford store on the corner of Main and Batchelor Streets. Twenty years prior, a young Tapping Reeve (1744-1823) traveled from New Jersey to Hartford to study law under a lawyer named Jesse Root (1736-1822). Reeve later moved to Litchfield where he established the Litchfield Law School, the first such school in the nation. A quick look at Root’s genealogy reveals a son, Jesse Root Jr., who is listed as a merchant in Hartford.

Fire buckets were a different kind of utilitarian item: used sparingly, but highly visible. Buckets were usually stored or hung near the entrance of a house, often in plain sight of visitors. Because they also needed to be marked with the owner’s name, fire buckets presented an opportunity to turn a plain-looking item into a work of art. Many were decorated with fancy lettering, family crests, patriotic motifs, and other painted scenes. Members of fire companies and mutual societies took pride in owning fire buckets emblazoned with the organization’s name and symbol.

The tradition of decorating fire buckets provided additional business for local sign painters and artists. Today, fine examples of painted fire buckets are valued as folk art as well as pieces of firefighting history, and frequently command high prices at auction.

Come back next week learn about another object that will be featured in our newest exhibit, Antiquarian to Accredited, opening in 2020.