It’s long been a challenge for those researching ancestors who may have been illiterate, poor, or marginalized to learn about their heritage. Institutions like the Litchfield Historical Society were founded and began collecting during the Colonial Revival, a time when there was tension over immigration and clashes between races, classes, and nationalities. Our founders were the descendants of wealthy white immigrants from Western Europe who wished to preserve their history by saving their ancestor’s decorative arts, artifacts, and papers, predominantly those of men.

While we continue working to make our collections more representative and inclusive of all the people who made Litchfield home, a lot of the town’s early history of women, minorities, and the natives displaced by the settlers was lost, or perhaps never documented at all.

In spite of these challenges, there are places to turn for evidence. Probate records (Litchfield’s Probate Court is in the basement of Town Hall) are a valuable resource. The estate inventory, along with the written will, may contain reference to people who worked for or were enslaved by the deceased. Property records (also in Town Hall) are an option if your ancestor owned land or a home, and phone directories (we have these for select years) may also provide an address. Census records (many online) are another valuable place to turn, although you will find different information in different decades. Court records like writs or indentures are another possible resource. (We have some court records, but the most comprehensive collections are in the State Archives).

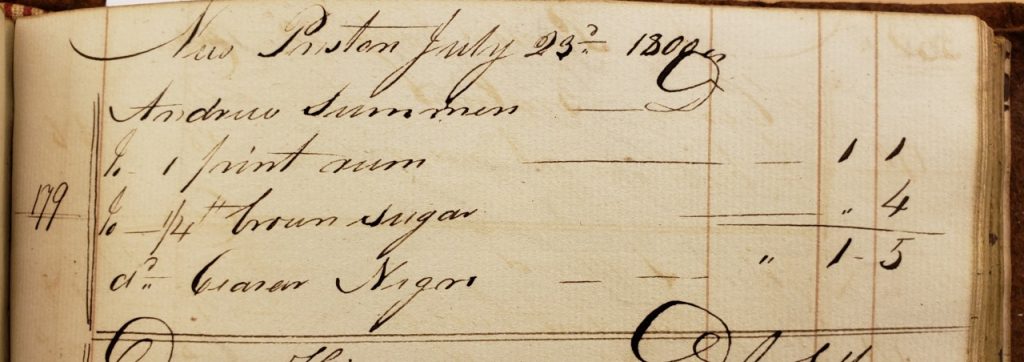

There are also options that can seem more like scavenger hunts. The indexes for early accounting ledgers sometimes contain headings like “Negro” under which are listed all of the African Americans who did business with a particular merchant. The names will lead to the daybook in which the entry was made, and you might find what someone purchased. Sometimes they contain nothing other than a first name and something that was bought or bartered by the individual. Other times, they include the name of the person’s enslaver or employer. As we move forward with describing collections, we are adding these details to our description.

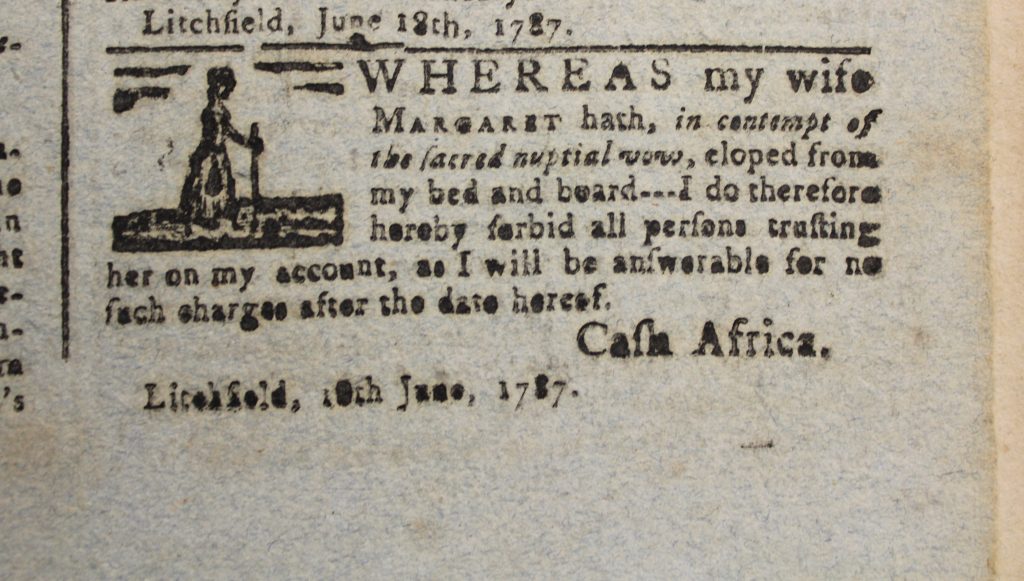

Another great source for information is newspapers. They often contained advertisements for “runaway” humans, be they wives or enslaved or indentured members of households. While we have Litchfield papers going back to the 1780s, they are not indexed or available online, with a few exceptions. Issues of the earliest paper, the Litchfield Monitor, are available through the Early American Newspapers database. Although they are in the public domain, they are behind a paywall. The Connecticut State Library has recently announced that they have received funding to digitize issues of The Litchfield Enquirer and the Litchfield County Post which they will add to the Connecticut Digital Newspaper Project.

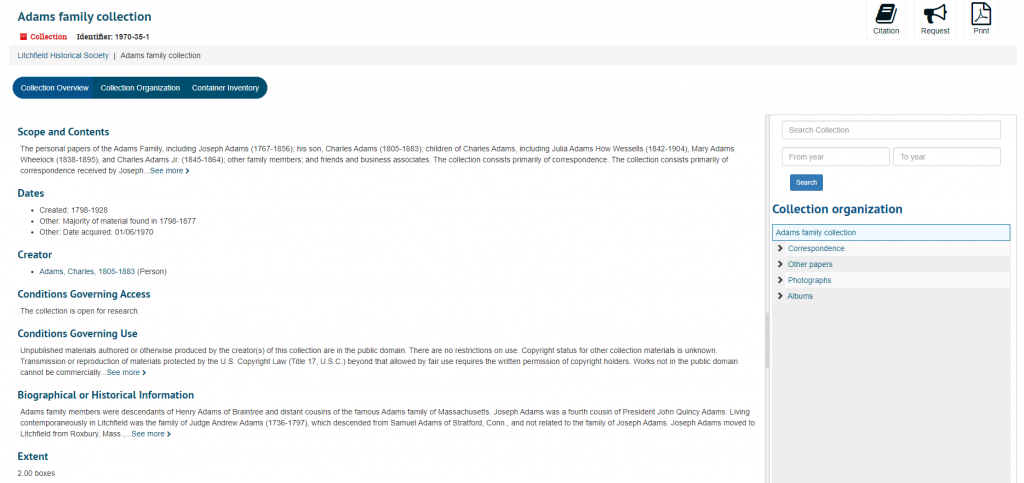

Having a basic understanding of archival description will also aid you in your search. Archivists are often responsible for describing large aggregates of material, and do so using a tool called a Finding Aid. (For more on Finding Aids see The Hows and Whys of Finding Aids by Dorothy Berry and Betts Coup.) It is rare to find item-level description, in part because the context of the entire collection is what gives individual items meaning. This can make it a challenge for those trying to locate evidence of a person who may only be mentioned once within the collection. Finding aids include a description of the collection, notes about how the repository acquired it, and what staff has done to the materials since acquisition.

There are already some guides available that help users navigate available sources, though many are repository specific. A few more general guides include The National Archives: Genealogy Ethnic Heritage Links; the Library of Congress Bibliography & Guides.

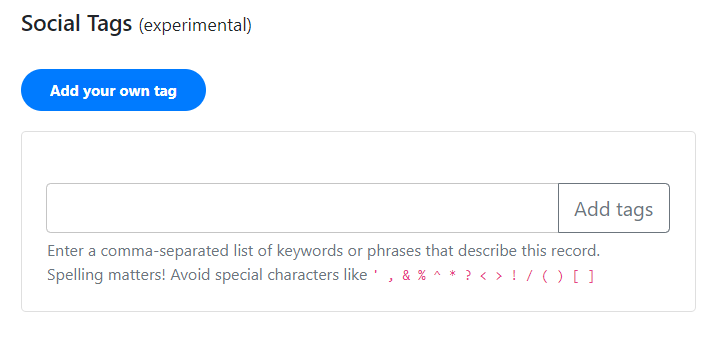

The words you use when searching also matter, as does spelling. Keyword searches in our databases aren’t “smart.” In order for you to find alternate spellings, the description must include all of them. If you aren’t familiar with controlled vocabularies or subject terms, they may also provide barriers to finding what you seek. One effort we have made in hopes of breaking down that barrier is a social tagging tool available in our artifact catalog. To find a good example, I searched for my favorite garment. I think some might describe it as a robe, so that’s the term I used. It didn’t appear in the six pages of results. I searched again by the term I know it’s described with, “dressing gown.” It was the second item on the results page. If you click that link, you’ll see the object page with a button to “add your own tag.” Clicking on it opens a box where users can enter words they would use to describe an artifact. Staff are then able to approve the suggestions thereby improving search results.

The more documents we are able to transcribe and the more artifacts we are able to tag, the better access we can give to the small bits of information which may provide the only evidence of someone’s life in a particular place. Archival practice has traditionally relied on describing aggregates, and it is important to provide and preserve the context of materials, but it is equally important to provide more granular access to materials that our users cannot locate any other way. Archival workers are now able to employ tools that can involve other stakeholders in the descriptive process, through the use of social tagging tools, crowdsourced transcription (where scans of documents are available online for volunteers to transcribe), and open sharing of collections and descriptions to create richer and more personal experiences for users. Though we are a small repository, we are working to employ tools developed as open source by larger places as part of our efforts to improve the accessibility of our collections. This can be a slow process as these projects are often dependent upon grant funding, but we are committed to continued improvement.

Keep in mind that these suggestions and ideas are based on what we have seen in the Historical Society’s collections. I hope others who have done this kind of work will weigh in with their ideas and helpful tips. I do hope that you will reach out to ask for help if you are having difficulty navigating our finding aids; finding evidence of your ancestor; reading the handwriting; or have any other barrier to access that we can help you overcome. While it may take us some time to get the answer, particularly during the pandemic, we will do our best to help you find what you seek. We also welcome any additional suggestions about how we can make our collections more accessible.