Written by Bill Bucklin

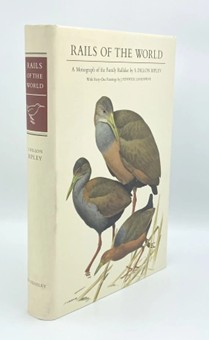

Lying on its side among the shelves of old leatherbound volumes, the big book with three stately birds on the front cover practically begs you to pick it up. Rails of the World: A Monograph of the Family Rallidae by S. Dillon Ripley is not about railways, but about Ripley’s favorite subject–birds. From a review by Roger Tory Peterson: “Among the least known and most elusive of any major bird species, rails manage to colonize remote islands, impenetrable jungles and desolate shorelines in almost all regions of the world.”

The book is a window into the world of S. Dillon Ripley, one of Litchfield’s most fascinating residents. Rosemary Ripley, his daughter, said in an interview: “My father was interested in birds from a very young age. My grandmother was a single mother. She decided to take the family to live in India for a year. My father was 13 and living there opened his eyes to the natural world.”

Ripley continued his interest in bird species as a teenager in Litchfield in the 1920s. Later he became a professor of ornithology at Yale University, served as Director of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, and in 1964 became the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. His greatest contribution to Litchfield is the Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy, which he and his wife founded in 1985.

S. Dillon Ripley died in 2001 and is buried in Litchfield’s East Cemetery, but his legacy is very much alive in Litchfield.