Contributed by Leith Johnson, Project Archivist

Among the women and men who settled the Connecticut Western Reserve in the early 1800s were students of the Litchfield Law School. To get an idea of the impact these individuals had on the development of the territory, I selected one student more or less at random and researched his life and the lives of his children. What I am going to sketch out here is by no means comprehensive, but it does offer an illustrative case study. Much of what I am writing is taken directly from The Firelands Pioneer, a journal first published in 1852 by the Firelands Historical Society, that is an indispensable resource for information about the settling and development of the area farthest west in Western Reserve known as the Firelands.

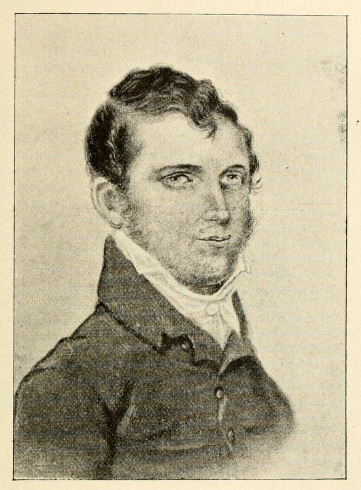

David Gibbs was born in 1788 in Windsor, Conn., a son of Capt. Samuel Gibbs, who served in the Revolutionary War and then was involved in shipping, and Engeltje (Nancy) Harsin Gibbs. When David was 14, the family moved to Norwalk, Conn. He graduated from the Litchfield Law School in 1808 and two years later, he married Elizabeth Lockwood, daughter of Stephen and Sarah Betts Lockwood also of Norwalk. With a view to practicing law in the newly opening west, he and fellow lawyer Charles Robert Sherman made a trip to the Western Reserve in 1811, which had begun to be settled around 1807. Sherman stayed, but Gibbs returned to Connecticut to accept a position in Bridgeport. When the War of 1812 broke out, he enlisted and was given a commission as first lieutenant in the 37th Regiment, Infantry.

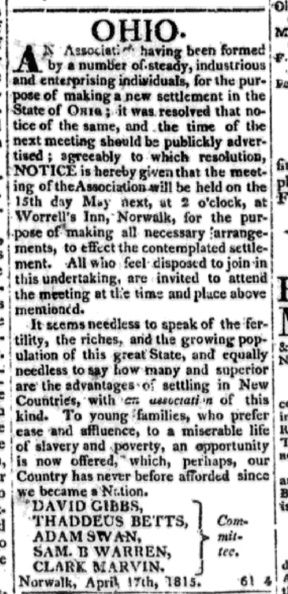

But the pull west remained with Gibbs, and in 1815, he and with four others in Norwalk announced the formation of an association to foster a settlement in Ohio in an advertisement they placed in the local newspaper, which declared in part:

“It seems needless to speak of the fertility, the riches, and the growing population of this great State, and equally needless to say how many superior advantages there are of settling in New Countries, with an association of this kind. To young families, who prefer ease and affluence, to a miserable life of slavery and poverty, an opportunity is now offered, which, perhaps, our Country has never before afforded since we became a Nation.”

I did not find out what became of this association, but that year, he, his brother-in-law Henry Lockwood, and father-in-law Stephen Lockwood made a return trip. They spent 10 weeks looking for a suitable place to settle and decided on Norwalk, Ohio, located in the “Sufferers’ Lands” (as the Firelands were originally called), which the Connecticut state legislature had set aside to provide financial restitution for residents of the state towns—including Norwalk—whose homes had been burned in 1779 and 1781 by British forces during the Revolutionary War. Stephen Lockwood owned a large tract there. They spent several months on their homestead, beginning work on the construction of a double log cabin and clearing land and laying in a crop of wheat. Then, they returned to Connecticut and their families.

The following January 1816, David and Elizabeth Gibbs, their daughter Eliza, age five, and son David, age three; Henry Lockwood and his family; and a teamster set off from Connecticut to start a new life in Ohio. There must have been a good reason for leaving in the middle of winter, but I have not found out what it was. They traveled in two covered wagons, one pulled by two yoke of oxen carrying all of their household goods and supplies and one that appeared to be comfortably equipped, according to this description found in The Firelands Pioneer:

“Mrs. Gibbs and Mrs. Lockwood, with their children, were provided with a substantial wagon, covered with oil cloth, lined with blankets, carpeted and provided with spring seats; very comfortable and decent and drawn by a heavy span of bay horses. They were well clothed and provided with abundant blankets and a foot stove. Their provision chest contained cold chickens, hams, hard biscuits, pies, doughnuts by the bushell, tea, coffee, pickles, dried fruit, preserves, and all the necessary et ceteras; so they were ‘well-to-do’ in the world.”

The trip was uneventful until February or March (the accounts disagree) when disaster struck. The supplies wagon broke through the ice while crossing a river west of Buffalo, N.Y. One yoke of oxen died and all of their household goods went to the bottom of the river. Nearby friendly Native Americans assisted them, “who, by diving and fishing with poles, brought up most of the lost articles, among them a box of log chains, axes, plowshares, kitchen ware, etc.” They also brought up the carcasses of the two oxen, which they accepted as compensation for their help. One account of the incident states that they were also given $30 or $40.

Things got much worse. While they remained there for about two weeks drying their goods and obtaining another team, Henry Lockwood’s young son fell ill and died. As they journeyed on, three-year-old David Gibbs came down with what was called “camp dysentery” and died two weeks later. Elizabeth Gibbs and daughter Eliza were also severely afflicted, and the trip was halted for six weeks as they recovered enough to resume the journey. Elizabeth was carried to the wagon and rode on a bed. The unforeseen expenses and delays cost them $500, which in 1816 was a very large sum of money. In April, 95 days after leaving Norwalk, Conn., they reached Norwalk, Ohio.

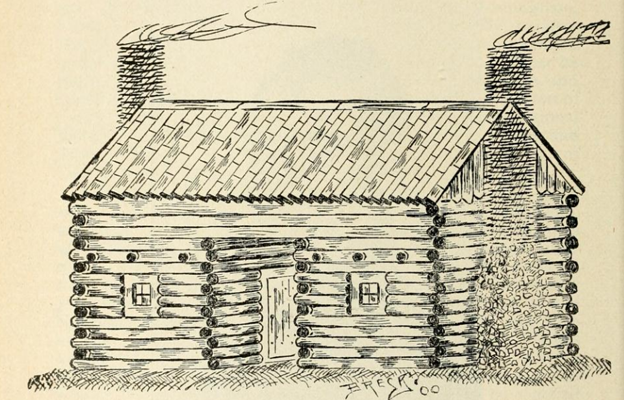

The Gibbs and Lockwood families moved into the double log house that had been waiting for them since the previous fall. It was the fourth house built in Norwalk. With a covered passageway through the center, there were front rooms on each side that were 18 feet square, with bedrooms back about eight- or nine-feet square, and a small pantry. Sleeping rooms were in the upper loft, divided by hanging partitions. There was a cellar underneath that often flooded after a brisk rain. The small windows were at first covered with greased paper instead of glass. The doors were rough slabs split out of logs, and their first table was a square, with no leaves, hewed out of a black walnut log. On his farm was a never-failing spring on which the few neighbors depended for their supply of drinking water. The nearest neighbor lived one-and-a-half miles north on the road.

“Mrs. G. often remarked that their rude double log house ‘looked to her like a palace,’” The Firelands Pioneer wrote, “and it subsequently bore the same enchanting appearance to many a weary pioneer who was the recipient of the kindness and good cheer of its occupants. It was the headquarters, or rather the home, of all the numerous acquaintances, and many others, emigrating to this region in those early days. At one time, for nearly two weeks, their families were increased to forty souls, of whom nine were down with the ague! For all this numerous family Mrs. G. did the cooking, baking, etc., with rude and limited utensils, designed for less than one-fourth of that number; whilst Mrs. Lockwood ministered to the sick with means for their comfort equally limited.”

Life was not easy. “At times they experienced much inconvenience from the scarcity of and difficulty in obtaining the staples of flour and pork. They subsisted one week on milk and potatoes alone.” Religious meetings were held at a home miles away. To attend, “generally, they went on horseback, Mr. G. occupying the saddle with a child in his arms and Mrs. G. sitting behind him having another in her lap. Few of the pioneers could afford this luxury, but had to go on foot or be drawn with oxen.” In 1823, he built a wood frame house that still stands today (although moved from its original location), apparently the oldest house in Norwalk.

Gibbs had an active civic presence in his new town. In 1817, he was one of the petitioners to form the township of Norwalk and was elected as its first justice of the peace. In 1820, he was a founder of the local chapter of the Masons. In 1823, he was on a committee to establish an educational institution, the Norwalk Academy, that opened in 1826. Among the school’s many graduates were his sons and future president Rutherford B. Hayes. He was appointed county clerk in 1825, a position he held for the rest of his life. In 1837, he served as president of the board of directors of the Female Institute, founded in 1837. He died in Norwalk in 1840. Elizabeth Lockwood Gibbs died there in 1873.

The United States Census of 1850 gives us a snapshot of the fortunes of David and Elizabeth Gibbs 34 years after settling in Norwalk. That year, she and her children (more on them below) had combined real estate holdings of $27,350 (to put that in perspective, a day laborer in 1850 would have had to work 29 years to earn that much money) and that amount does not include any non-real estate assets. Clearly, the family had made the most of their investment in Ohio.

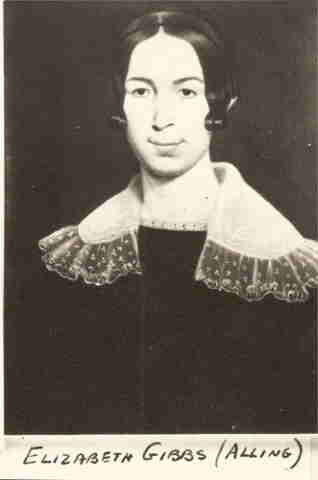

David and Elizabeth Gibbs had ten children, but only seven made it to adulthood. Eliza Gibbs Alling (1811-1904) was born in Connecticut and survived the arduous trip west. The rest were all born in Norwalk, Ohio: David Gibbs Jr., 1817-1897; Roswell Gibbs, 1818-1880; Charles Gibbs, 1821-1891; James B. Gibbs, 1822-1850; Ralph M. Gibbs, 1824-1854; and Sarah Louise Gibbs Mowry Adams, 1835-1934.

I looked into the lives of each of the children, curious about how the next generation made out in the Western Reserve.

I wasn’t able to find much on Eliza Gibbs Alling (1811-1904). Beyond the sickness she endured traveling to Ohio, all I know is that she married Prudden Alling (1808-1879). The Firelands Pioneer called him a “businessman,” but he was much more than that. He arrived in Norwalk from New York state in 1833, and by 1835, he had already been involved in at least two ventures in town. That same year, he traveled to Chicago to size up business opportunities there, deciding that most everything was overpriced. A week after he returned to Norwalk, he married Eliza. His firm, P. Alling & Co., was the wholesaler of Stanley’s Rotary Stoves and other hardware items. When his father-in-law David Gibbs died in 1840, he took over Gibbs’s former position as county clerk and assumed ownership of the Gibbs family homestead, the location of which eventually became known as Allings Corners. In 1850, no less than 14 Alling and Gibbs family members were living there. The censuses of 1850 through 1870 listed his occupation as farmer, which he took great interest in, along with much more. In 1848, at the county agricultural fair, he was awarded the first premium on corn production. In 1855, he was listed as owner of two 40-acre parcels in Jasper, Iowa. (I haven’t been able to determine what became of these.) In 1857, he was cofounder of a factory that made cultivators, which unfortunately failed after one year due to an economic downturn. He received two patents, one for a combined vine cutter and garden cultivator in 1868, and one for a seed-planter in 1870. He died in Norwalk in 1879 and Eliza died there in 1904. They had eight children.

David Gibbs Jr. (1817-1897) held several different positions. He worked along side his father as deputy county clerk prior to moving to Troy, Ohio, by 1850, where he was a lawyer. By 1860, he had moved to Harris, Ohio, and was a miller. During the Civil War, he was a captain of a company in the 21st Ohio Infantry Regiment. By 1870, he was an insurance salesman in Elmore, Ohio, and in 1880 he was the cashier of a national bank in LeMars, Iowa. At this time, cashier was second only to bank president in importance to the organization, serving as the person who ran the bank on a day-to-day basis. He was also the city treasurer of LeMars. He died there in 1897. (I don’t know why he went to Iowa, but I think there’s some significance that he seemed to follow in the family tradition and moved farther west.) He married Eliza Bacon Gibbs in 1843 and they had five children.

Roswell Gibbs’s (1818-1880) career also took him into banking. In 1850, he was living with his brother David and family in Troy and was a clerk in some form of business. By 1860 he had a position as a bank cashier. In 1865, he was a cashier in Shelby, Ohio, but in 1870 he was back as a cashier in Troy, where he died in 1880. He married Mary Jay Gibbs in 1850 and they had six children.

Charles Gibbs (1821-1891) entered Hamilton College in New York at age 13 and then went to Kenyon College in Ohio, where he graduated and became a tutor. He thought of going into law, but instead turned to religion and attended the Yale Theological Seminary, receiving a license to preach, but ill-health prevented him from regular work. He was a principal of an academy in Wisconsin, but his health forced him to leave after a year. He went back to Ohio and lived with his brother-in-law in Troy, became a civil engineer, and was elected as county surveyor. But his devotion to religion remained strong. He returned to preaching when his health permitted, eventually moving to Iowa, as his brother David had, to serve as a pastor in churches there, ending up in Cedar Rapids, where he died in 1891. He married Lovina Campbell Gibbs in 1869 and they had one child.

James Gibbs (1822-1850) also heard the religious calling. He attended Yale University and the Yale seminary, graduating in 1844. He returned to Ohio and preached for several years before taking up further study in Hudson, but was stricken with tuberculosis and died in Norwalk in 1850. He did not marry.

Ralph Gibbs (1824-1854) was a clerk living in nearby Milan in 1850. I suspect he might have gone on to a successful career in banking or business like two of his brothers, but he died in 1854, a victim of one of several cholera epidemics that swept through the region, which, as one old resident recalled in the Firelands Pioneer, “raged in virulent form, and in some instances almost whole families were swept out of existence.” He married Mary Higgins Gibbs in 1846 and they had four children.

Sarah Louise Gibbs Mowry Adams (1835-1934) was a life-long member of the Presbyterian Church, a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, a life member of the American Tract Society, and a member of the Firelands Historical Society. She also held membership in the D.A.R. and was given an honorary membership in the Ohio Society of the Daughters of 1812 (she was one of the few surviving actual daughters, since her father served as a lieutenant in the war). Commonly referred to as “Louise” in the records, she married Augustus Mowry in 1857, a merchant living in Milan who had come to Ohio from New York. He died of typhus in 1859. They had one daughter who died at age 16. In 1868, she married William Augustus Adams. He had been a farmer until 1866, when he sold out and moved to Hudson to educate his children. His first wife’s death occurred in 1866 in Milan, where he lived for the next two years. After marrying Sarah, he promptly bought a large farm in Clarksfield. In 1882, they moved to the little town of Eaton Rapids, Mich., which was known in the late 1800s for its mineral water baths, considered to have health benefits and cure ailments (perhaps the Adamses wanted to relax?). William and Sarah had a daughter, but she also died at age 16. Louisa returned to Norwalk in her later years and died there in 1934.

Research on other Litchfield Law School students who migrated to the Western Reserve would tell us how typical the story of David Gibbs and his children is, but despite the hardships of resettlement, sickness, and untimely death, this family, at least, seems to have thrived in Ohio.

A note about sources:

For accounts of the Gibbs family journey from Connecticut to Ohio and their early years there, see:

The Firelands Pioneer, vol. XI, Oct. 1874, 83-85. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSD3-4QFP-F?cat=299185)

The Firelands Pioneer, new series vol. IX, Oct. 1896, 105-108. (https://archive.org/details/firelandspioneer91fire/page/n116/mode/1up)

The Firelands Pioneer, new series vol. XII, Dec. 30, 1899, 542-552. (https://archive.org/details/firelandspioneer12fire/page/542/mode/1up)

For a genealogy of the descendants of David and Elizabeth Lockwood Gibbs, see:

The Firelands Pioneer, new series vol. XII, Dec. 30, 1899, 542 552. (https://archive.org/details/firelandspioneer12fire/page/542/mode/1up)

History of the Fire lands, comprising Huron and Erie Counties, Ohio… by William W. Williams (1879, Cleveland, Ohio : Press of Leader Printing Company, 124-126) also contains an account of the Gibbs family journey and settlement, based entirely on the 1874 The Firelands Pioneer article, but includes some additional bits of information.https://archive.org/details/historyoffirelan00will/page/124/mode/2up

The United States Census 1850-1930 was used to chart occupations, residence locations, and family relationships.

In addition to these specific sources, The Firelands Pioneer published obituaries and articles relating to some family members and a brief description of cholera in Norwalk. Other sources consulted included published and online genealogies, U.S. Patent Office records, newspapers, 19th century publications, and Findagrave.com.