The Litchfield Historical Society will host a lecture by the Calder Foundation on June 5, 2021, in the Tapping Reeve Meadow. To celebrate that partnership and the life and work of Alexander Calder (1898-1976), we are going inside the collection to look at one of the Society’s most intriguing works of art.

Alexander Calder was born into a family of artists. His mother was a trained painter, and his father and grandfather were accomplished sculptors. Beginning his career with illustrations and paintings, Calder experimented with wire sculpture before moving to Paris in 1926. In France, he began work on the Cirque Calder, a body of articulated wire sculptures designed to be performed for an audience. Calder performed and evolved his Circus for a number of years in both Paris and New York. Many of Calder’s early kinetic sculptures were moved using motors—it was fellow artist Marcel Duchamp that first dubbed these moving sculptures “mobiles.” Soon, Calder stopped using motors and began creating sculptures that would move freely in the air.

In 1933, Alexander and his wife, Louisa, purchased a home in Roxbury, Connecticut. While they remained world travelers, the Calders left a rich legacy in their adoptive state.

Calder Comes to Litchfield

To understand how the Society came to own this wonderful piece, we have to begin in 1949. That year, Litchfield residents Rufus and Leslie Stillman visited the “House in the Museum Garden,” a full-scale modern home constructed in the sculpture garden of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Convinced that modern design was the right path for their own home in Litchfield, the couple sought out and commissioned the house’s architect, Marcel Breuer. Equally renowned for his achievements in architecture and furniture design, Breuer studied and taught at the famed Bauhaus school in Germany before coming to America, where he established an architectural firm in New York.

Breuer’s first project in Litchfield was “Stillman I,” completed in 1950. The project ushered in a productive period of modern design in Litchfield, including both private homes and civic buildings. Thanks in part to introductions made by Rufus and Leslie, Breuer’s designs were joined by those of John Johansen, Edward Larrabee Barnes, Edward Durell Stone, and other modern architects.

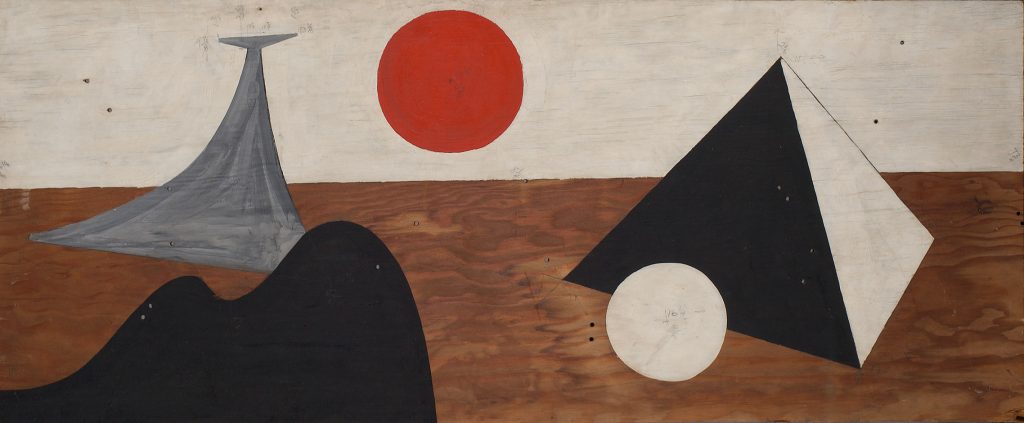

It was Breuer who introduced the Stillmans to Alexander Calder. The architect even added one of the artist’s colorful mobiles above the open stairwell in the Stillmans’ new home, one of multiple Calder originals owned by the couple. In 1951, Calder designed and executed a mural on the freestanding wall screening one end of the home’s pool. Variations of the design were added to the two subsequent homes that Breuer designed for Rufus and Leslie. In time, the Stillmans donated a maquette from the pool mural, the hooked rug seen above, and other Calder pieces to the Litchfield Historical Society.

Designing Rugs for the Stillmans

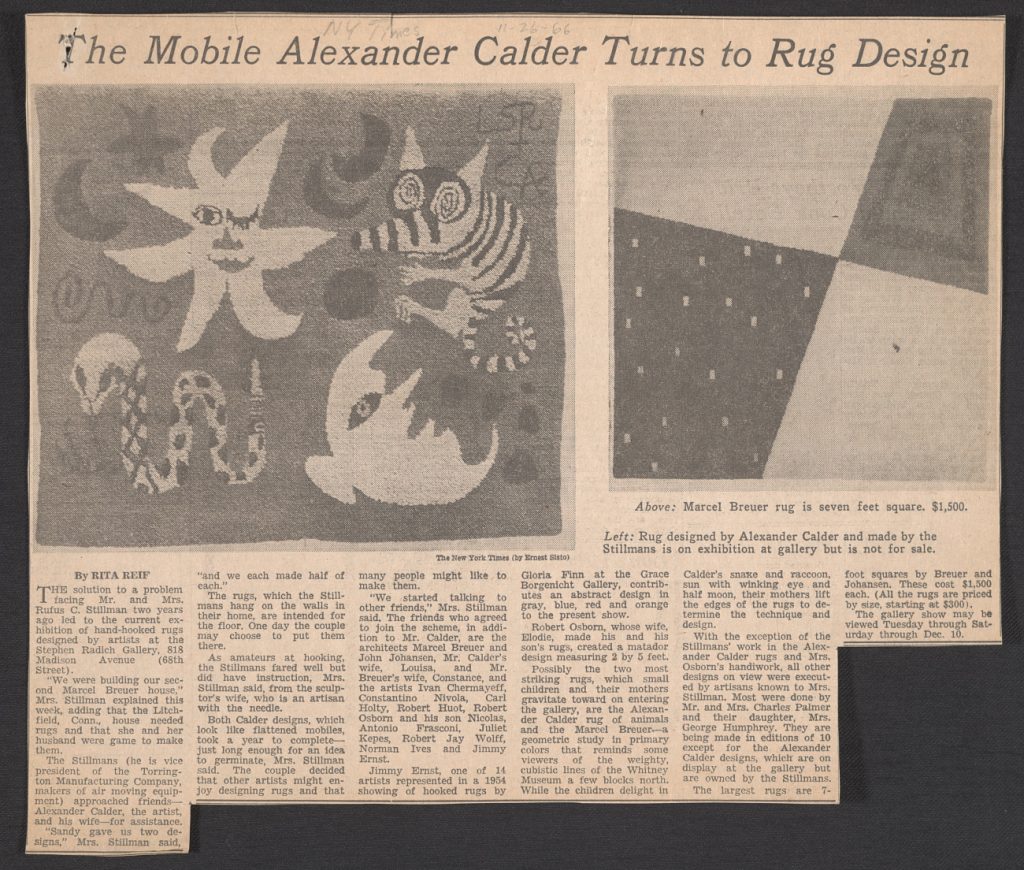

The hooked rug in our collection is one of two known Calder designs produced by the Rufus and Leslie. In November 1966, an article appeared in The New York Times to promote an exhibit of rugs organized by Stillmans. According to Leslie, the idea for the exhibit came about when the two were building their second Breuer-designed home in Litchfield. The home “needed rugs and…she and her husband were game to make them.” The Stillmans approached the Calders for assistance—Alexander provided two rug designs, and Louisa provided instruction in hooking the rugs. The Stillmans each completed half of each rug over the course of a year, long enough for the couple to decide that “other artists might enjoy designing rugs and that many people might like to make them.”

Among those who contributed rug designs for the exhibit were Marcel and Constance Breuer; fellow architect John Johansen; and artists Ivan Chermayeff, Robert Osborn, and Robert Jay Wolff, all of whom are represented in the Society’s collection. Artisans known to the Stillmans and the designers hooked each rug by hand. The rugs were produced in editions of ten and offered for sale, except for the two Calder designs which remained in the possession of the Stillmans. Calder’s striking animal rug (illustrated in the article, below) was donated by the Stillmans to the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut.

Fiber Arts in France

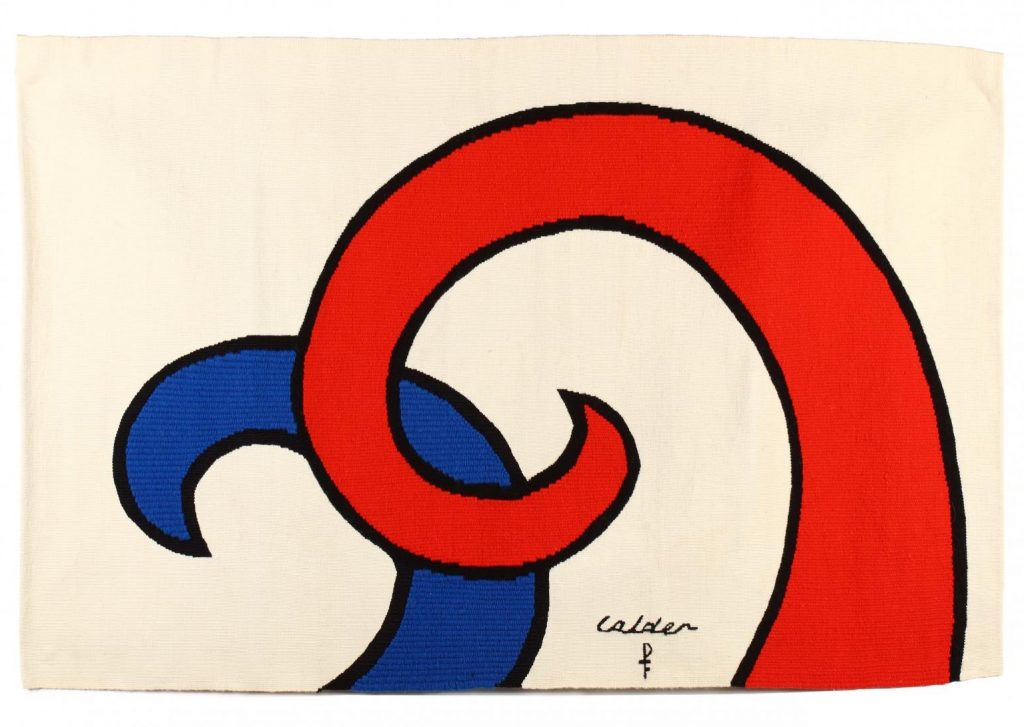

In addition to their Roxbury home, the Calders kept a home and studio in Saché, France. In the 1960s and 1970s, Calder developed designs in ink and gouche to be realized as wool tapestries by expert weavers in nearby Aubusson, France. Produced by ateliers such as Raymond Picaud and Pinton Frères, most of the tapestries were executed in Australian wool and dyed to Calder’s specifications. To mark the occasion of America’s Bicentennial in 1976, a special series of Calder designs were commissioned for Aubusson tapestries. Though smaller and generally less complex than the earlier examples, the Bicentennial tapestries were produced in greater numbers.

Examples of the Aubusson tapestries appeared in Calder retrospectives at the Guggenheim in 1964 and the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1965 and formed the basis of an exhibit at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1971. A review of the Whitney exhibit appeared in The New York Times in October 1971. It concluded, “the colors are pure Calder—rich blacks, brilliant reds, sunny yellows and snowy whites. The slight increase in rigidity inherent in tapestry technique is welcome in patterns increased to several times the size of the freely executed models. Everything works together with complete success.”

The Calder Foundation website contains a wealth of information on Calder’s life, including a timeline of his career and an archive of works. Click here to visit.