This trip “Inside the Collections” features another object on display in our 2021-2022 exhibit, Antiquarian to Accredited: A Look Inside the Historical Society. The embroidery seen below is a “found in collection” object, meaning we do not know how or when it came into our collection. Usually given to the Society at a time when we had limited recordkeeping, found in collection objects are rarely attributed to a creator or owner. This piece was no different.

At first glance, the embroidery reminded me of a woolie. What is a woolie, you ask? Woolie is a common name for a sailor’s woolwork picture, a folk art tradition centered on embroidered images of ships, nautical scenes, and patriotic motifs.

Woolies

Most sources agree that woolies originated with British sailors in the first half of the nineteenth century, and remained popular from about 1840 to World War I. As a folk art form, woolies represent the coming together of three factors: free time, sewing skills, and sentimentality. Facing long hours at sea and in port, sailors likely turned to embroidery as a way to pass the time, keep their hands busy, and differentiate their working and leisure hours, similar to other maritime folk arts such as scrimshaw and knotwork. For as long as sailing ships dominated naval and merchant fleets, sailors were also required to possess rudimentary sewing skills, as one of their duties was to repair and maintain the ship’s sails. Sailors also mended and embellished their own uniforms, requiring them to keep sewing supplies on hand. Lastly, woolies served as mementos of a sailor’s service and travels or as gifts for loved ones upon his return. The number of woolies that survive from this period suggest they were prized possessions. Examples in period frames may even indicate that the sailor or his family made a monetary investment to have the woolie displayed.

The primary subject matter was ships, usually a single vessel shown broadside with full sails and large, unfurled flags. Some ambitious embroiderers did include multiple vessels, or place the ship within a detailed landscape scene showing a foreign port, naval battle, or ship in distress. While British examples predominate, American-made woolies begin appearing later in the nineteenth century. The majority of woolies are unsigned, but some examples are dated or initialed. Many include the name of the pictured vessel or enough clues (gun ports, signal flags, rigging, etc.) to identify the period and origin of the ship. Larger and more elaborate woolies were likely worked by sailors on land or after returning home, as they would have been difficult to complete and store while at sea.

Some of the materials used to create woolies were readily available on a ship, including the sailcloth, linen, or cotton fabric used as a ground for the embroidery, and the wood used for the stretcher. Some sailors preferred a ground of embroiderers’ canvas, which allowed for more delicate stitching but would need to be brought from home or purchased in a foreign port. Most used wool thread for the embroidery (hence woolwork or “woolie”), but cotton and silk are also common. As embroidery thread was not kept on board, it too would need to be purchased ahead of time or during shore leave. According to an article in Antiques & Fine Art Magazine by Katherine E. Manley, the yarn texture evidenced in a small number of woolies suggests that sailors occasionally “unpicked and reused the wool of discarded garments” to make their pictures. Surviving woolies reveal a variety of stitches and embroidery techniques, including cross stitch, chain stitch, long stitch, darning, and trapunto, a quilting technique used to create a raised or high relief surface.

Embroideries as Souvenirs

A number of factors led to the declining popularity of traditional woolies in the early nineteenth century. The advent of steam engines in commercial and naval vessels decreased the size of most crews and the level of sewing skills needed by each sailor. Photography provided an alternative and less time-consuming method of capturing memories while at sea. Beginning around the turn of the century, sailors also had the option of buying a ready-made “woolie” produced by embroidery shops in Japan and other countries in Asia. While these commercially-made souvenir embroideries or needleworks looked drastically different to traditional sailors’ woolies, their bold colors and intricate stitching make them a worthy art form in their own right.

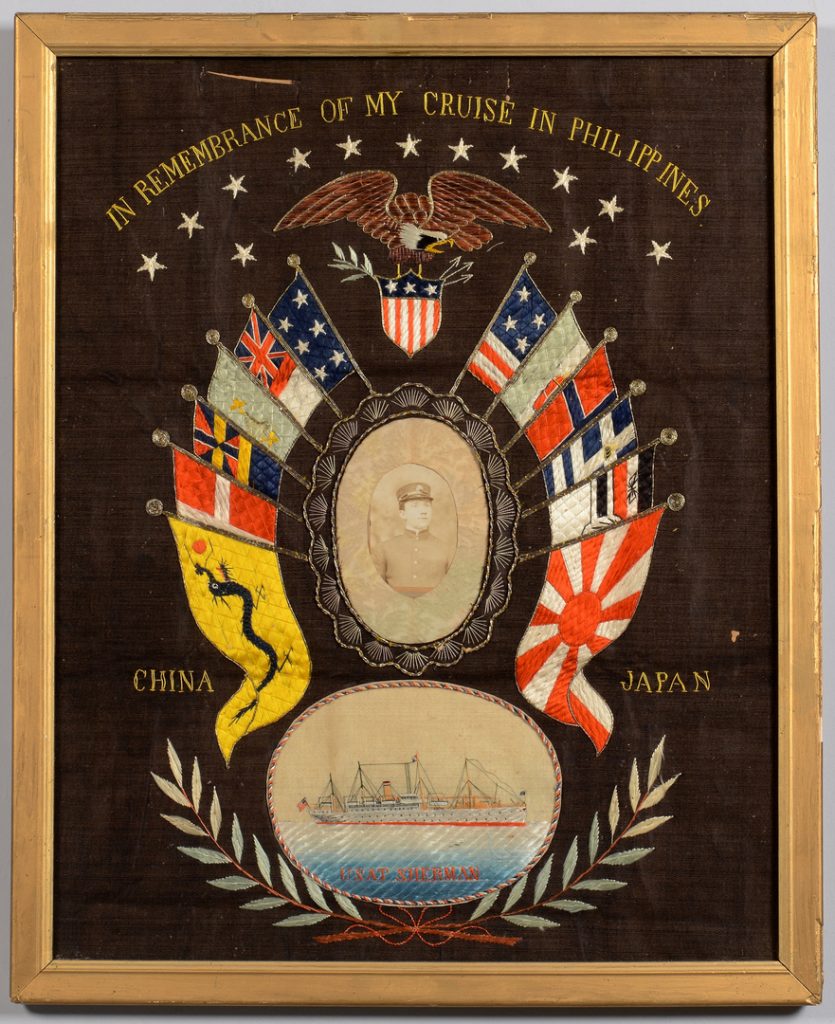

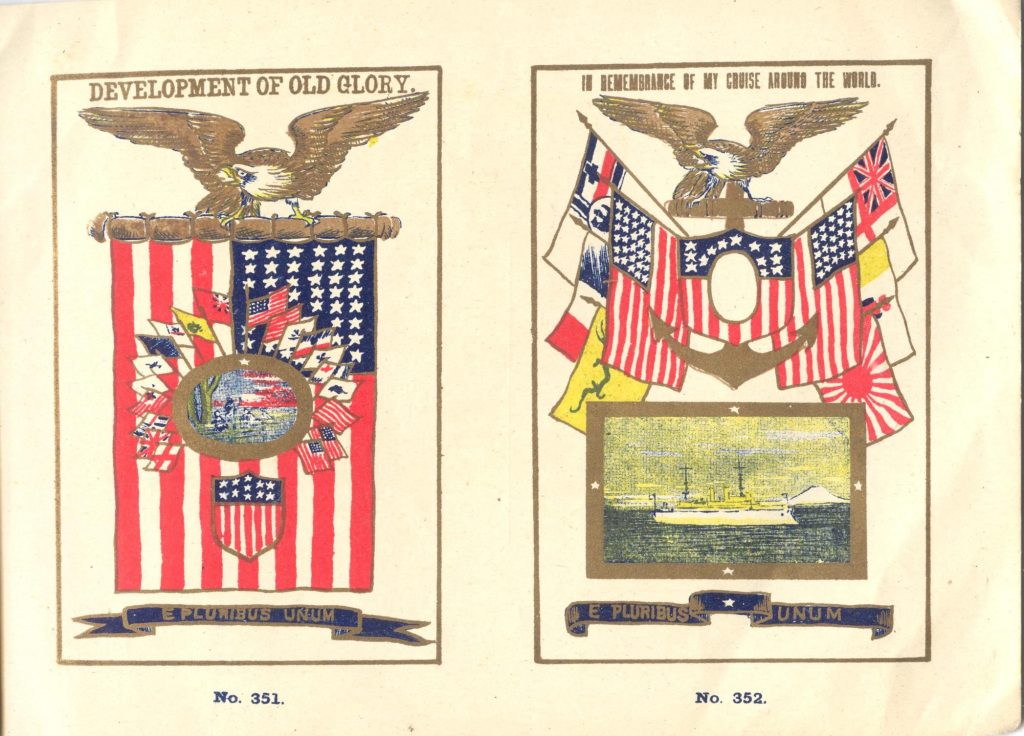

Because they share a number of commonalities, these souvenir embroideries are instantly recognizable. Almost every needlework features an eagle (either a large eagle prominently placed in the center or a smaller version towards the top) perched on a shield bearing the American flag, two decorative elements pulled directly from the Great Seal of the United States. The embroideries are usually titled with a variation of “In Remembrance of My Cruise Around the World” or a cruise to specific counties, with China, Japan, the Philippines, and Hawaii being most common. Other elements include anchors executed in metallic thread, banners bearing the motto “E Pluribus Unum,” rows of embroidered flags from different nationalities, and decorative motifs such as stars, wheat, and florals.

In keeping with the woolie tradition, most souvenir embroideries featured a smaller ship’s portrait executed in stitching and watercolor and placed in a “porthole” towards the bottom of the piece. They also commonly feature evidence of a new innovation: photography. As seen in the examples above, souvenir needleworks included a small opening in which sailors could place their own photograph. Some embroideries made to commemorate the Great White Fleet, which sailed around the globe between 1907 and 1909, even included photographs of President Theodore Roosevelt and Admirals Robley Evans and Charles Sperry.

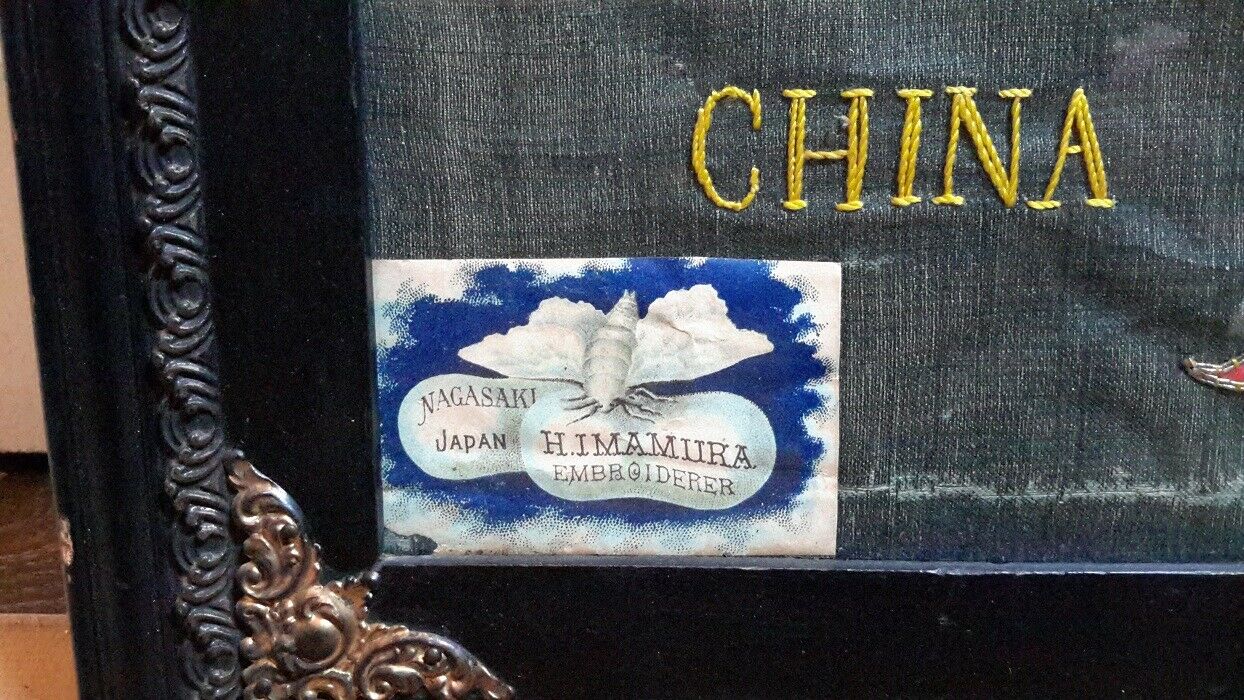

As a whole, souvenir embroideries were more patriotic in design than traditional woolies, and were largely targeted to American sailors. Identified embroidery shops in Yokohama, Nagasaki, and Tokyo produced large numbers of these needleworks, and even offered illustrated catalogs from which sailors could choose their preferred pattern. One of the more well-documented shops was the George Washington Company of Yokohama, which sold a number of items popular with American sailors including kimonos, tablecloths, shawls, oil on canvas paintings, calendars, and Christmas cards. The embroideries were largely completed ahead of time; sailors could add personal touches such as photography and retrieve the finished piece in a matter of days.

Because these embroideries were produced in large numbers, they frequently show up at auction. Use terms such as “eagle silk embroidery,” “Japanese silk souvenir embroidery,” and “trapunto banner” to see more examples.

Further reading:

“Woolies Ahoy!,” Raymond M. Lane, Washington Post, June 13, 1999: LINK

“Stitches of History,” Katherine E. Manley, Antiques & Fine Art Magazine; LINK