My favorite way to pick a new “Inside the Collections” topic is to stumble upon it—in this case, to come across it while housing new acquisitions in our storage facility. We have well over 20,000 objects in our museum collection, stored in seven rooms in three different buildings. Even after nine years at the Historical Society, I regularly “find” objects for the first time, or find a reason to reconsider an object I haven’t seen for some time. Sitting on one of the many shelves in our open storage area, I paused for a few seconds on two pieces of thin, pressed metal with obvious connections to England (see below). While they are clearly decorative, even so far as having evidence of a painted surface, I couldn’t immediately place their function. Too small to be an effective business sign, but too large to be a nameplate. The database told me they are “insurance signs.”

The more specific answer is that they are insurance markers. To be even more precise, fire insurance markers or, simply, fire marks.

That these two examples are English is telling—fire markers began appearing in England in the seventeenth century, following the Great Fire of London in September 1666. Seeing a need (or opportunity) to sell protection against future disasters, English entrepreneurs formed new insurance companies, laying the groundwork for modern property insurance. These companies offered incentives to clients who took their own fire prevention measures, such as opting for brick construction over wood. The companies also formed their own private fire brigades to respond to fires at their clients’ properties, which in turn helped minimize the company’s insurance payouts. But how would the brigades know which houses were insured by their company? By looking up.

Insurance companies began to issue fire markers to their clients, who would then place them in a visible location on their homes or businesses. Often made of cast or pressed metal, these markers were decorated with the name and/or emblem of the issuing insurance company; sometimes they were also stamped with the client’s policy number. As an added benefit, the marks served as advertising for the company and a way to mark their “insurance turf.” Even as firefighting in England moved away from private companies over time, fire markers continued to serve this advertising role.

By the time insurance companies began forming in America in the mid-eighteenth century, the colonies already had a well-established tradition of volunteer fire brigades. This distinction, however, did not keep fire markers off of colonial structures. American insurance companies issued fire marks beginning in the 1750s. Similar to the English model, the markers served as a form of advertising, a sign of responsible property ownership, a notice to responding fire brigades, and a deterrent to arsonists who would fear being pursued by the company insuring the building.

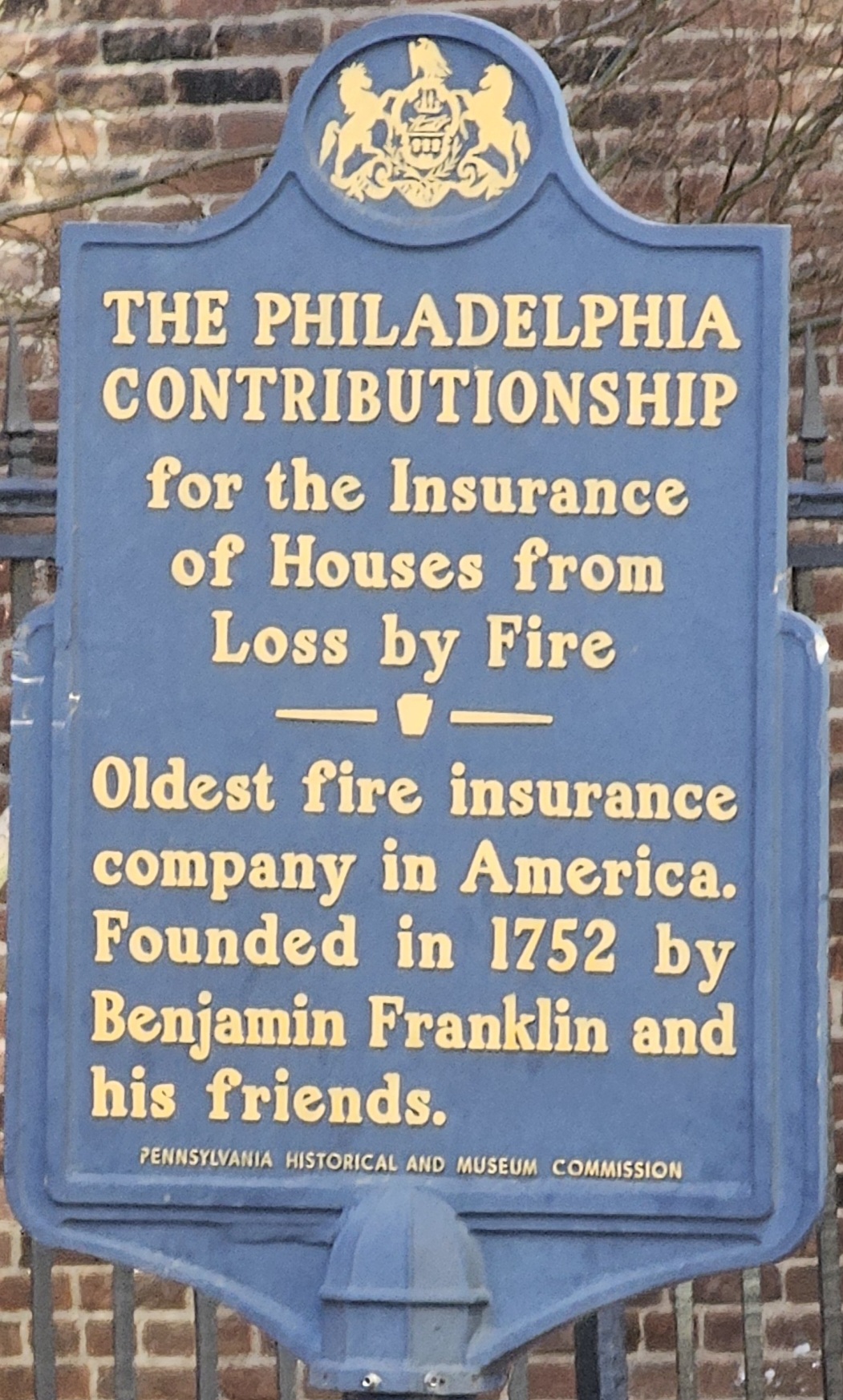

Fire marks fell out of fashion by the early twentieth century, but they remain an often overlooked part of our built landscape. Take a stroll through older streets in New York, Washington, D.C. (especially the Georgetown neighborhood), Baltimore, or Charleston, and you will likely come across one of these marks preserved on a building front. Fire marks are such a part of America’s architectural fabric that the designers of New Orleans Square in Disneyland (California) placed multiple markers on their building facades, including one for the Disneyland Fire Department (not exactly accurate for an insurance marker, but certainly they get credit for including this detail). One of the best cities for spotting fire marks is Philadelphia. No discussion of fire insurance in the United States is complete without mentioning the Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire, formed in 1752 by Benjamin Franklin and his associates. The Contributionship remains the nation’s oldest insurance carrier in continuous operation. Many of the buildings in Philadelphia’s Elfreth’s Abbey (one of the nation’s oldest continuously inhabited residential streets) maintain their insurance markers, placed above the first story to deter theft or tampering.

Society Hill neighborhood.

As the use of fire marks declined and their value as collector’s items rose, certain misconceptions or generalizations found their way into the history of insurance markers. For example, that a volunteer fire company would refuse to put out a building fire unless it had a visible marker, or that fire marks ensured a fire company would receive a reward from the insurer if they were the first to “put water on” an insured property. The former was likely influenced by the fact that English insurance companies did maintain private firefighting brigades. But in America, where volunteer fire companies became prominent social organizations championing public service, it is highly unlikely that firefighters would turn a blind eye to uninsured properties. It seems even less likely that insurance companies would accept a practice that endangered surrounding, and possibly insured, properties (keeping in mind that fires were rarely contained to a single building). And while there is evidence of municipalities and insurance companies paying rewards to volunteer fire companies, the practice was too irregular to be considered common practice, and not always tied to the presence of a fire marker.

While researching the use of fire insurance markers in Connecticut, I came across the above marker held in the collection of the National Museum of American History. It comes as no surprise that Hartford, nicknamed the “Insurance Capital of the World,” would have multiple companies issuing fire insurance markers. On the very first page of Charles W. Burpee’s A Century in Hartford: Being the History of the Hartford County Mutual Fire Insurance Company (1931) is an illustration of the above marker, referred to by Burpee as “an emblem of distinction.” The Company’s first insurance policy (and marker) was issued for the property of Preserved Marshall of Avon, Connecticut. As of 1931, it was still standing.

Petitioning the Connecticut General Assembly for a charter in 1830, the Hartford County Mutual Insurance Fire Company elaborated on the benefits of the “mutual insurance” model, in which the company exists solely to provide coverage for its policyholders. The petitioners argued that, “for the purpose of protecting their house and other buildings, in the country, from the ravages of fire, it would greatly promote their security and safety, and facilitate their views and operations, to be incorporated upon the principle of mutual insurance.” One of the key petitioners was Elisha Phelps of Simsbury, a lawyer, graduate of the Litchfield Law School, and member of the Connecticut House of Representatives. As originally formed, the Company was to insure only within Hartford County and outside of the city of Hartford “against loss by fire, whether by accident, lightning or any other means, excepting that of fraud or the design of the insured, or invasion or insurrection.”

The Hartford County Mutual Fire Insurance Company is not to be confused with the Hartford Fire Insurance Company, which was established in 1810 and is known today as The Hartford. Thomas Kimberly Brace, another graduate of the Litchfield Law School, was among the first directors of The Hartford and later founded the Aetna Fire Insurance Company in 1819.

Something about the size and design of the Hartford County Mutual’s insurance marker seemed immediately familiar, though a search of our museum collection database and collections inventory proved unfruitful. Convinced I had seen a similar marker at some point since joining the Historical Society, I headed to our storage facility for some old-fashioned “digging around.” The result can be seen below.

Litchfield’s very own fire insurance marker, modeled closely on the appearance of those issued by the Hartford County Mutual Fire Insurance Company. While not as decorative as those produced in Philadelphia or other cities (relying solely on painted lettering over pressed metal designs), this object is proof that insurance companies in more rural locations such as Litchfield County still adopted the practice of issuing insurance markers. It also provided me with a mission-related reason to further research this fascinating material culture tradition (and, I guess, catalog that “missing” Litchfield marker so others can find it).

Are you interested in learning more about fire insurance markers? Visit the Fire Mark Circle of the Americas to learn more about the work of signevierists (the term for those who study and collect fire marks). https://firemarkcircle.org/