Have you seen our very own Tapping Reeve popping up on Facebook a lot lately? I’m sure you’ve noticed him donning holiday outfits, dressing for the weather, and enjoying events around town. You may have even noticed that Mr. Reeve has started taking more frequent trips out of the state, which he has been kind enough to share with his friends through his travel photos.

One thing you may have also noticed through it all is that no matter what Tapping is up to he always has some very recognizable characteristics. It could be his iconic seated pose, with crossed legs and glasses in hand. Or it could be his shoulder length locks and high collar shirt.

But who is responsible for this recognizable image of Reeve? It is the only known image in existence of this noted American jurist and founder of the nation’s first law school. Without it we would not know today what this pioneering legal mind looked like. To the artist responsible for creating Reeve’s likeness we owe a debt of gratitude.

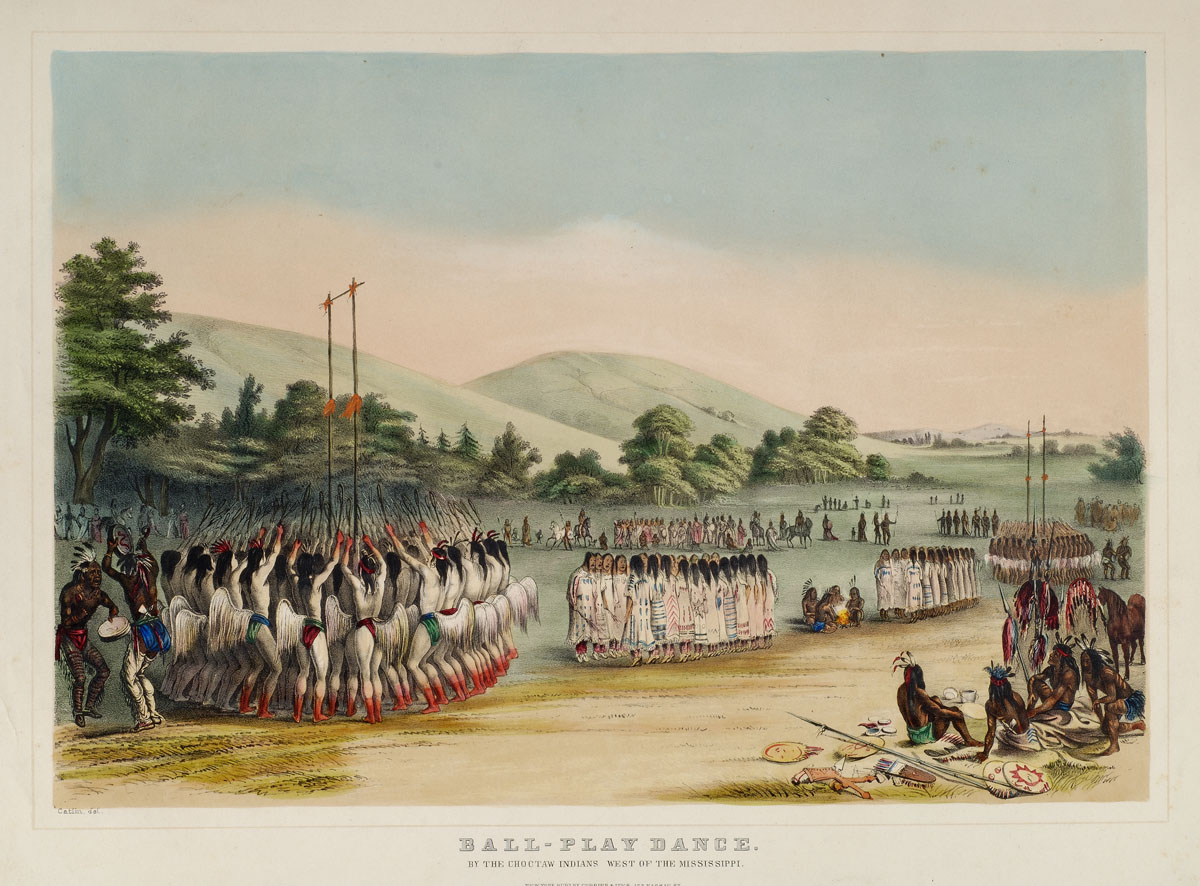

George Catlin is a name recognized by art historians, Native American scholars, and 19th-century history buffs alike. Remembered as the creator of a vast portfolio of artwork and writings documenting the lives, customs, and traditions of numerous Native American tribes, Catlin will go down in history as one of the great American artists who saw the importance of immortalizing the American frontier before it disappeared in the wake of industrialization and westward expansion.

Before beginning work on his life’s masterpiece however, George Catlin was a young law school student at the Litchfield Law School in 1817. While attending lectures Catlin was known for having more of an interest in sketching his fellow students and local scenery than working on his studies. He eventually passed his bar examination in Pennsylvania two years later and began a legal career. It was a short-lived stint however, as his love for art, nature, and natural history won out.

In 1821 Catlin moved to Philadelphia to pursue a career in art. He exhibited as a portrait miniaturist from 1821 to 1823 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, who accepted him as a member the following year. Following that honor he continued to work as a portrait artist in Pennsylvania before relocating his work to New York. Through the 1820s he produced numerous portrait miniatures as well as full-size portraits.

Watercolor on Ivory portrait miniature of Sarah Pierce. Attributed to George Catlin. Litchfield Historical Society.

Although Catlin left Litchfield after completing his legal studies, documentation exists in the Archives of American Art showing that Catlin was back in town in 1825—two years after Tapping Reeve’s death. In his subscription and expense notebook for 1825, Catlin writes:

“Having ascertained that my portrait of the Hon. Tapping Reeve is the only resemblance left of that memorable man, I have deemed it a duty to his friends and the public – and particularly to Gentleman of the Bar to propose the publication of it by Subscription

If published the plate will be executed in the most superb manner, and I hope that sufficient encouragement will be given in the way to authorize the execution of it.

The price of the prints will be one dollar each, to subscribers, payable on delivery. All other sale will be invariably at one dol. & fifty cents each.

Geo. Catlin

Litchfield 25th March 1825”

Following this entry is his subscription list containing twelve names, all but four from Litchfield. Among the subscribers were such notable legal and political names as Oliver Wolcott, Seth P. Beers, and Truman Smith, as well as Rev. Lyman Beecher. While the subscription list is not dated, it can be inferred from its placement in the notebook that it was compiled in 1825 during Catlin’s time in Litchfield.

Was the portrait of Reeve that Catlin mentions completed during his time in law school, or was it a piece that Catlin returned to Litchfield to complete for his former teacher? No one knows. And the location of the original is not known either. These are mysteries that have yet to be uncovered. What is known is that this portrait was turned into an engraving as Catlin proposed. The publishing of the picture did not happen until four years later in 1829. Why there was such a long delay is not noted by Catlin in his papers.

Portrait prints such as the one of Reeve were very popular in the United States prior to the Civil War. A market existed for the likenesses of politicians, businessmen, writers, and entertainers in the American home. Capitalizing on this demand, Catlin had already published two portrait engravings in Philadelphia prior to the publication of his portrait of Reeve in 1829. Utilizing his previous experience in marketing such prints, Catlin sought to transform another of his portraits into a print for buyers who may want to memorialize the Honorable Tapping Reeve. Working with Peter Maverick, an engraver in New York, Catlin was able to accomplish this goal.

As far as we know, neither Catlin nor Maverick recorded how many prints of the engraving Maverick produced. Was it a small handful—just enough to fill the subscription order taken in 1825? Or was it a much larger amount? Either way, Catlin and Maverick’s partnership to produce the print has left history with the only known image of Tapping Reeve. Without their work we would have to rely solely on the written record to piece together what this pioneering legal mind looked like. And Mr. Reeve would have a much harder time getting dressed for the upcoming holidays!

-Jessica Jenkins, Curator of Collections