The Historical Society began collecting in the 1890s, and was incorporated at that time. The first curator, Emily Noyes Vanderpoel, was the great-granddaughter of Benjamin Tallmadge. Members included descendants of Wolcotts, Demings, Tallmadges, and other early families of means. The Colonial Revival was in full swing, and veneration of one’s ancestors was all the rage. While we can thank these early members for preserving the records of the town’s past, there were certainly omissions. Whether through oversight or lack of available material, there remains little evidence of the African American and immigrant families who worked in Litchfield prior to the Society’s founding. Women are also underrepresented in the archives.

Little is not none, and our staff is making strides towards improving our description of materials that document the lives of underdocumented people. You’ll find examples of this in our finding aids (Tallmadge Collection here), as well as on our Tumblr log of the Elijah Boardman Papers project.

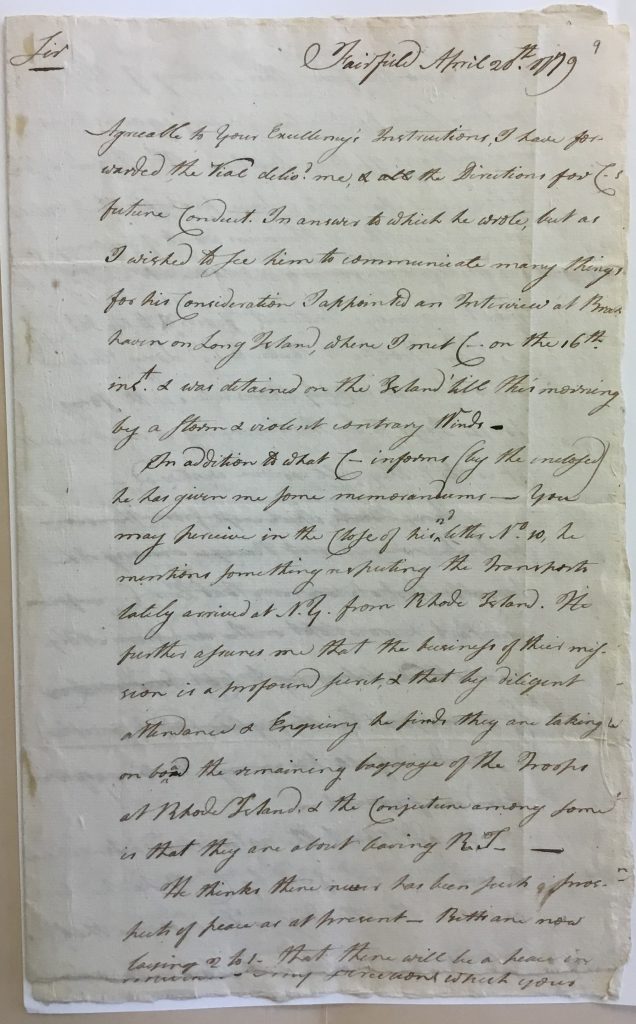

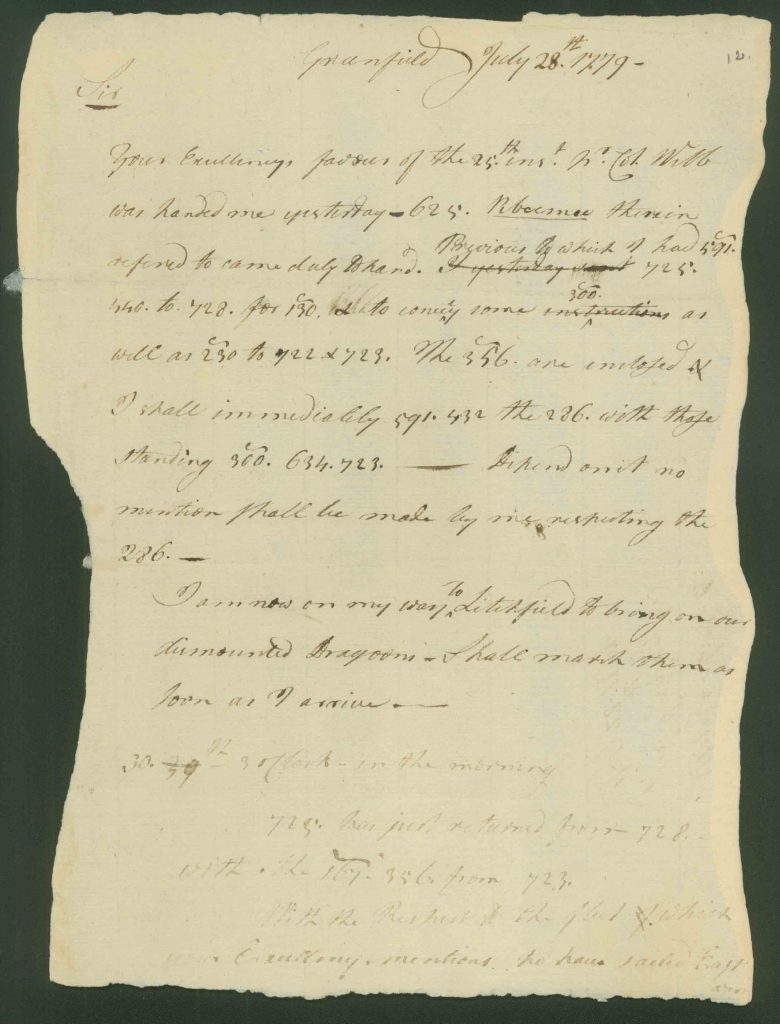

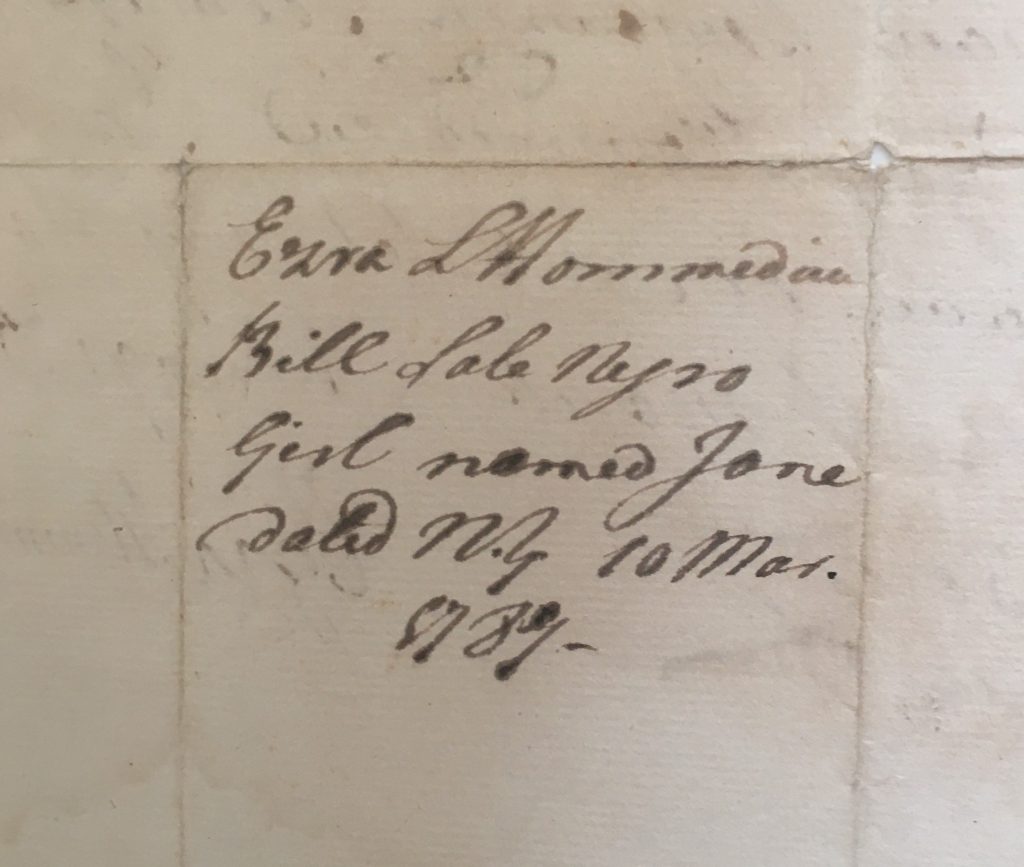

In this week’s Coffee with the Curator, I referenced a few receipts for the purchase of enslaved children. As we discuss Benjamin Tallmadge’s role in American History, we must note that he was an enslaver. Historian Lynne Templeton Brickley documented four enslaved members of the Tallmadge household, two indentured children, and a hired African American. The hired man, Cash Africa, as well as Tom Jackson, one of the enslaved, served in the Revolutionary War. There were other members of the household whose status was unclear. A number of Litchfield families, including the Deming, Wolcott, and Beecher households, included enslaved people and/or indentured servants.

Continue reading