The Historical Society began collecting in the 1890s, and was incorporated at that time. The first curator, Emily Noyes Vanderpoel, was the great-granddaughter of Benjamin Tallmadge. Members included descendants of Wolcotts, Demings, Tallmadges, and other early families of means. The Colonial Revival was in full swing, and veneration of one’s ancestors was all the rage. While we can thank these early members for preserving the records of the town’s past, there were certainly omissions. Whether through oversight or lack of available material, there remains little evidence of the African American and immigrant families who worked in Litchfield prior to the Society’s founding. Women are also underrepresented in the archives.

Little is not none, and our staff is making strides towards improving our description of materials that document the lives of underdocumented people. You’ll find examples of this in our finding aids (Tallmadge Collection here), as well as on our Tumblr log of the Elijah Boardman Papers project.

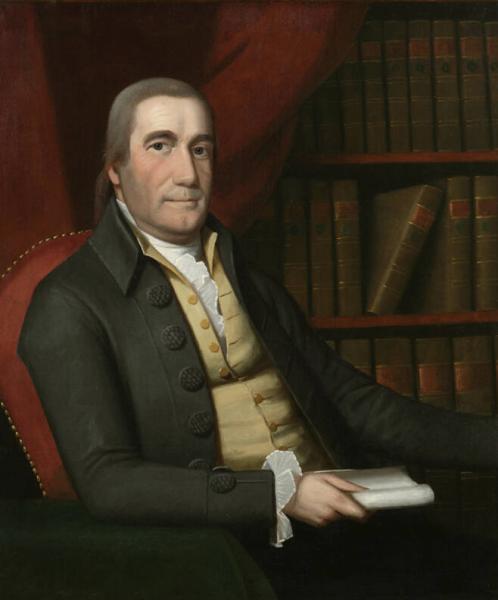

In this week’s Coffee with the Curator, I referenced a few receipts for the purchase of enslaved children. As we discuss Benjamin Tallmadge’s role in American History, we must note that he was an enslaver. Historian Lynne Templeton Brickley documented four enslaved members of the Tallmadge household, two indentured children, and a hired African American. The hired man, Cash Africa, as well as Tom Jackson, one of the enslaved, served in the Revolutionary War. There were other members of the household whose status was unclear. A number of Litchfield families, including the Deming, Wolcott, and Beecher households, included enslaved people and/or indentured servants.

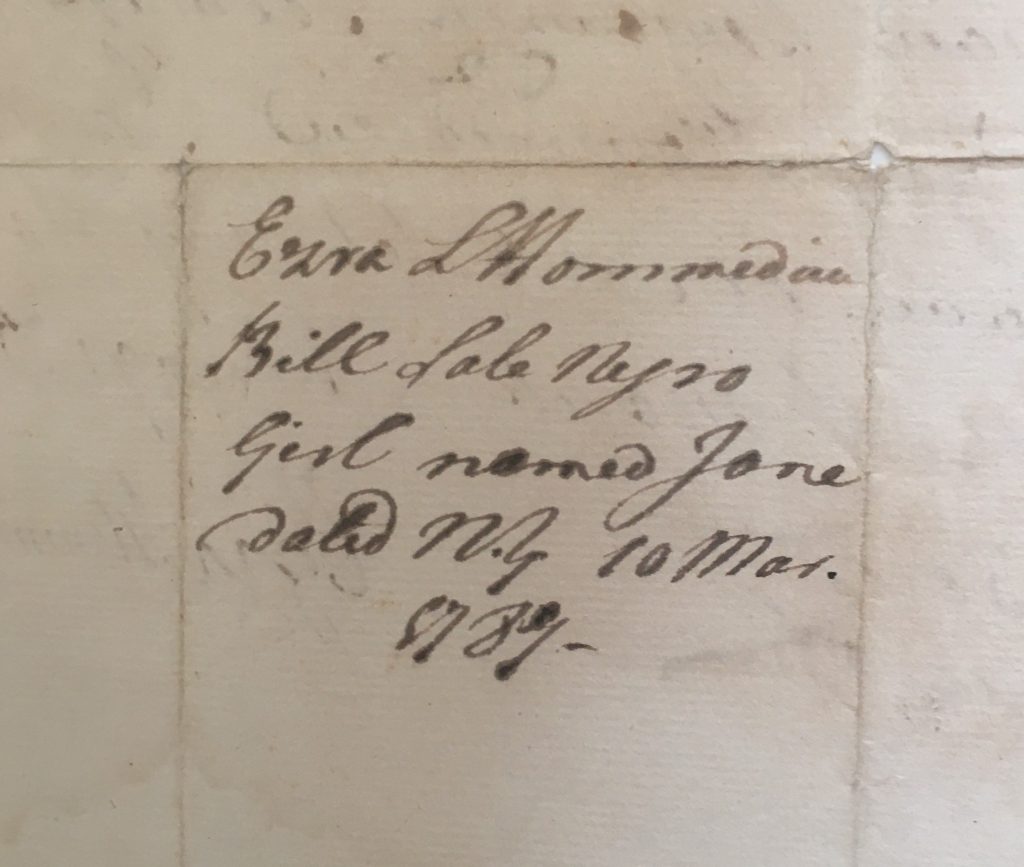

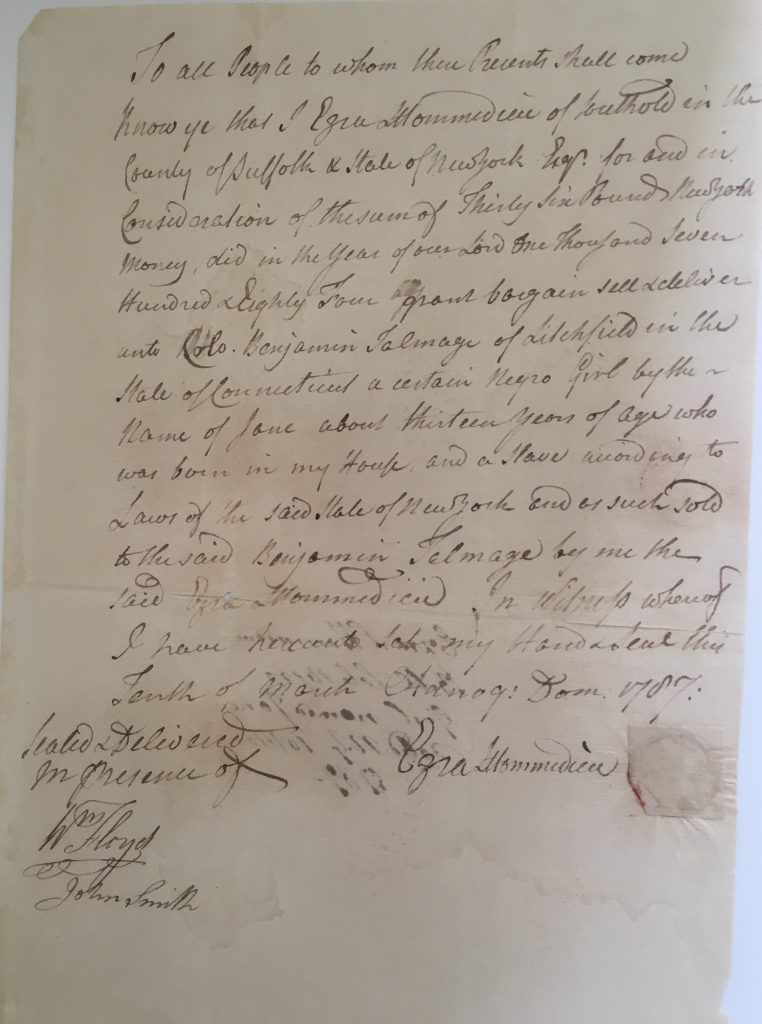

There are two documented instances of Tallmadge having purchased children, both the year of his marriage to Mary Floyd, the same year in which they moved to Litchfield. The first, Jane, a thirteen-year-old girl, was bought two days after the couple wed from Mary Floyd’s uncle Ezra L’Hommedieu for 36 pounds. Tallmadge noted in his memoir, “Soon after our marriage, we paid a visit to New York, where we found a great number of friends, with whom we spent a few weeks very pleasantly.” He didn’t mention purchasing a girl.

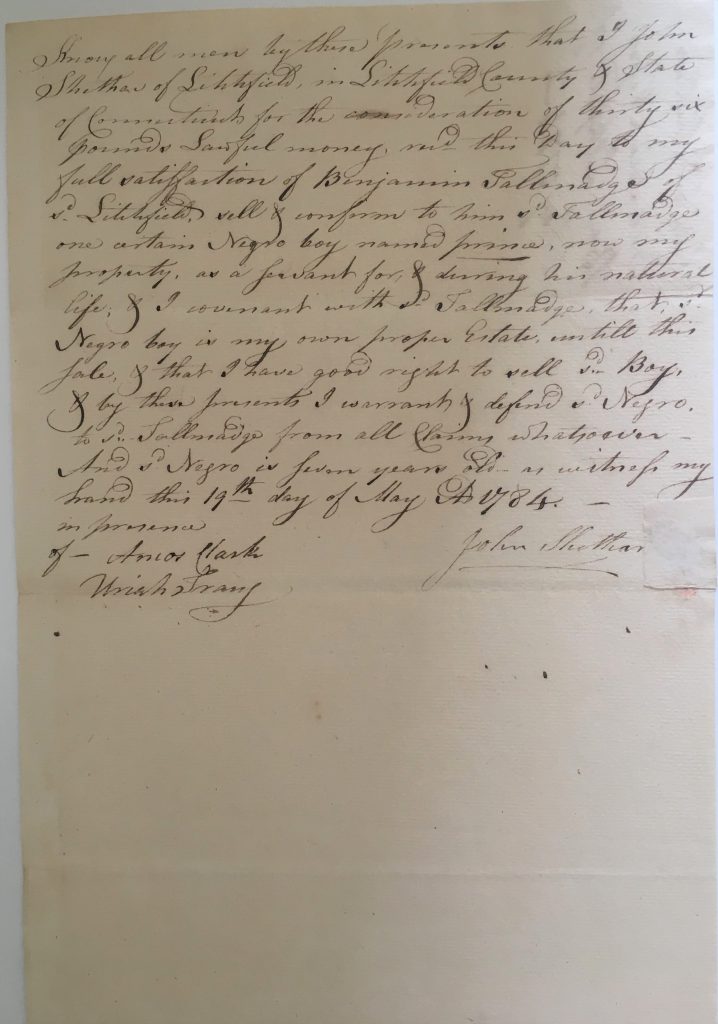

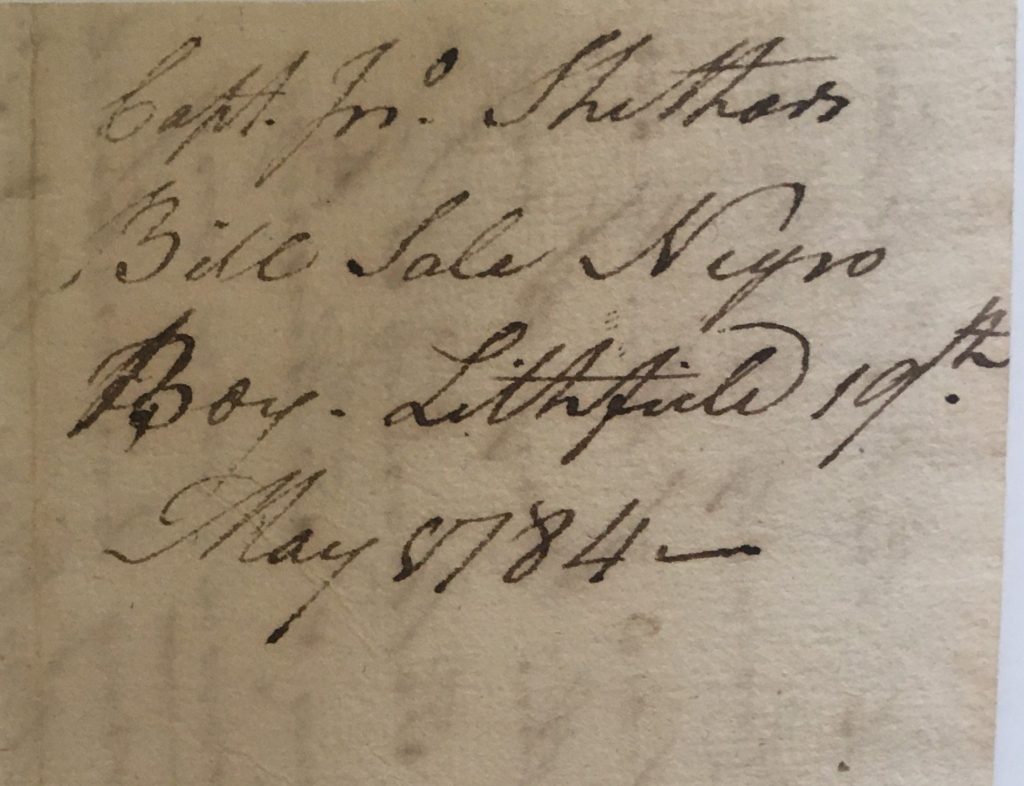

The second child, Prince, a seven-year-old boy, was purchased of John Shethar, also for 36 pounds. Shethar served in the same regiment as Tallmadge. His tri-cornered hat and sword are in the collection of the New York Historical Society.

I was able to find information and documentation of the lives of Ezra L’Hommedieu and John Shethar in under five minutes using Google. The lives of Jane and Prince remain relative mysteries. We know that Jane was born around 1771, and Prince around 1777.

After spending an hour trying to wrestle Google and various other search tools, I contacted Donnamarie Barnes, the curator/archivist of Sylvester Manor in New York. She provided me with the genealogy that clarifies the connection between the families, “Ezra L’Hommedieu was the great-grandson of Nathaniel Sylvester who with his brother and partners bought Shelter Island to establish a provisioning plantation for their sugar operations in Barbados in 1652. The L’Hommedieus were French Huguenots who settled in Southold and may have been connected to the Sylvesters through business. Benjamin L’Hommedieu married Nathaniel’s eldest daughter Patience.” Donnamarie kindly directed me to a collection of their papers housed at NYU.

Unfortunately, in terms of Jane, it was another dead-end. Although Donnamarie also pointed me to this list containing enslaved people held by Ezra, there was no mention of Jane. The papers do, however, contain some correspondence between Benjamin Tallmadge and Ezra L’Hommedieu which contain some interesting details about Tallmadge’s first wife. I’ll save that for another post.

Meanwhile, I’ll continue looking for Jane and Prince, and give an update if I find anything. The 1790 census entry for Tallmadge lists no enslaved persons. The 1820 census doesn’t either, though it shows one in the female under 14 years of age column under the heading “Free Colored Persons.”

Searching for information about African Americans, Native Americans, Women and other undocumented groups can be challenging. I am working on putting together some resources for researchers searching our collections. Stay tuned!