Note: This is part of an ongoing series of articles featuring objects from our upcoming exhibit, Antiquarian to Accredited: A Look Inside the Historical Society, opening in 2021. Check back often for new objects and articles!

One of the joys of my job is working with a material culture collection that is small enough to effectively manage, but large enough to still surprise me. For our upcoming exhibit, Antiquarian to Accredited: A Look Inside the Historical Society, we are featuring objects that both illustrate the diversity of our collections and tell unique stories. I went searching through our art racks for an interesting portrait that had rarely, if ever, been on display. Amid racks of familiar faces, I came across a well-executed portrait of a young woman with a famous name: Margaret Fuller, the noted author and feminist. Curious as to how the portrait came into our possession, and hopeful that I could find a connection between Fuller and Litchfield, I knew I had found the right piece for the exhibition.

Who was Margaret Fuller?

A full estimation of Fuller’s work and accomplishments is too long to describe here, even despite her relatively short life. She was born Sarah Margaret Fuller in 1810 in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. Her education began with her father, a Harvard-educated lawyer and congressman, who had Margaret translating Latin by the time she was sent to school in 1819. Fuller began writing for publication in her mid-twenties, with her mind set on traveling abroad and compiling a biography of the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

The death of her father in 1835 changed the trajectory of Fuller’s career. Hoping to support her widowed mother and siblings, Margaret took teaching posts at two short-lived, experimental schools: Amos Bronson Alcott’s Temple School in Boston and the Greene Street School in Providence, RI. It was around this time that Fuller was first introduced to Ralph Waldo Emerson and joined him in what came to be known as the Transcendental Club. By 1839 she was living outside of Boston, where she earned money by leading a series of Conversations, informal talks on various topics that were offered by subscription to Boston’s many well-educated women. Fuller elaborated on the nature of her talks in a letter to Sophia Riley in 1839:

But my ambition goes much further. It is to pass in review the departments of thought and knowledge, and endeavor to place them in due relation to one another in our minds. To systematize thought, and give a precision and clearness in which our sex are so deficient, chiefly, I think, because they have so few inducements to test and classify what they receive. To ascertain what pursuits are best suited to us, in our time and state of society, and how we may make best use of our means for building up the life of thought upon the life of action.

Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli, ed. R. W. Emerson, W. H. Channing, and J. F. Clarke (Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1852), 324-26.

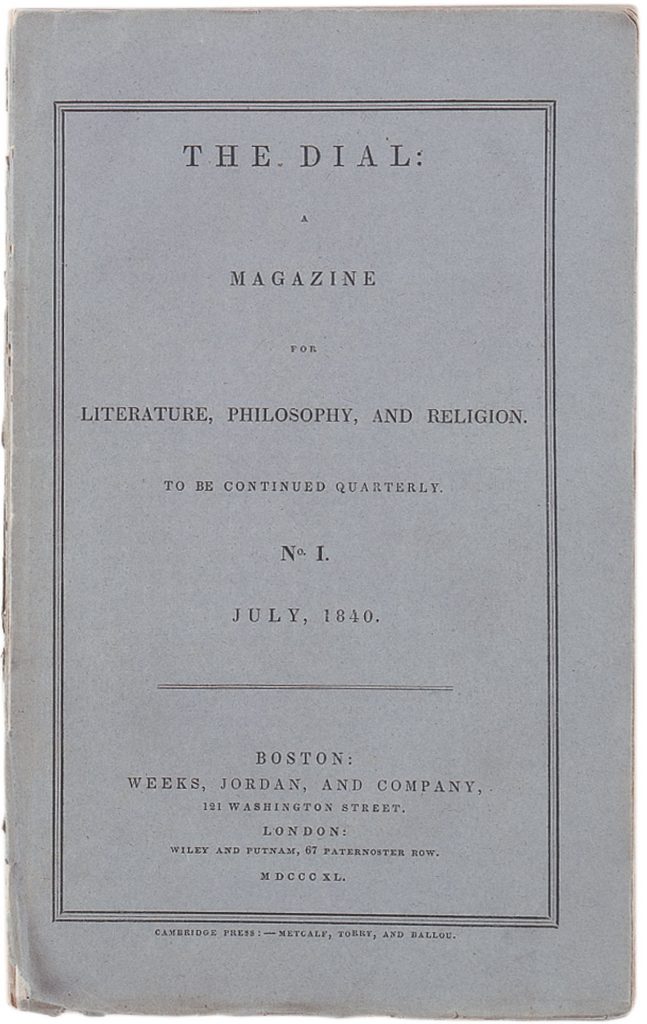

Fuller and Emerson founded The Dial in 1840, a literary and philosophical journal and the chief publication of the transcendentalists. Fuller was a regular contributor and edited the magazine until 1842. Her essay, “The Great Lawsuit,” appeared in the magazine’s fourth issue and laid out an argument in support of equal intellectual and social opportunities for women. The essay formed the basis of Fuller’s seminal book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, often considered the first major work of feminism in the United States.

In 1844, Fuller moved to New York to work for Horace Greeley, founder and editor of the New-York Tribune, where she served as the paper’s literary editor. She published more than 250 articles during this period, covering everything from art exhibitions to the urban poverty she witnessed in the city. In 1846, she set sail for England to serve as the paper’s first female foreign correspondent. In London, Fuller met Giuseppe Mazzini, an Italian activist living in exile after a series of failed attempts to effect the unification of Italy’s independent states, and after a brief stay in Paris she traveled to Italy and settled in Rome in 1847. Her time in Italy was short but eventful: she fell in love with a young marchese named Giovanni Angelo Ossoli, bore his son, and chronicled the rise and fall of Mazzini’s Roman Republic in 1849 (during which she worked at a hospital treating republican troops).

In May 1850, after four years in Europe, Margaret Fuller set sail for America with Ossoli and their son, Angelino. After two months at sea, and only a few hundred yards from the beaches of Long Island, their ship was caught in a storm and ran aground on a sandbar. The Ossoli family drowned as the ship sank beneath the waves, with only Angelino’s body recovered.

Is that really Margaret Fuller?

One of the difficult aspects of working with older segments of the collection is that our paper trail is often sparse, incomplete, or missing entirely. The accession records for this portrait do not indicate who donated the piece or, more importantly, why the sitter was identified as Margaret Fuller. Unless further information can be found, the validity of the attribution must remain in question. Let’s take a look at what we know (and don’t know) about the portrait.

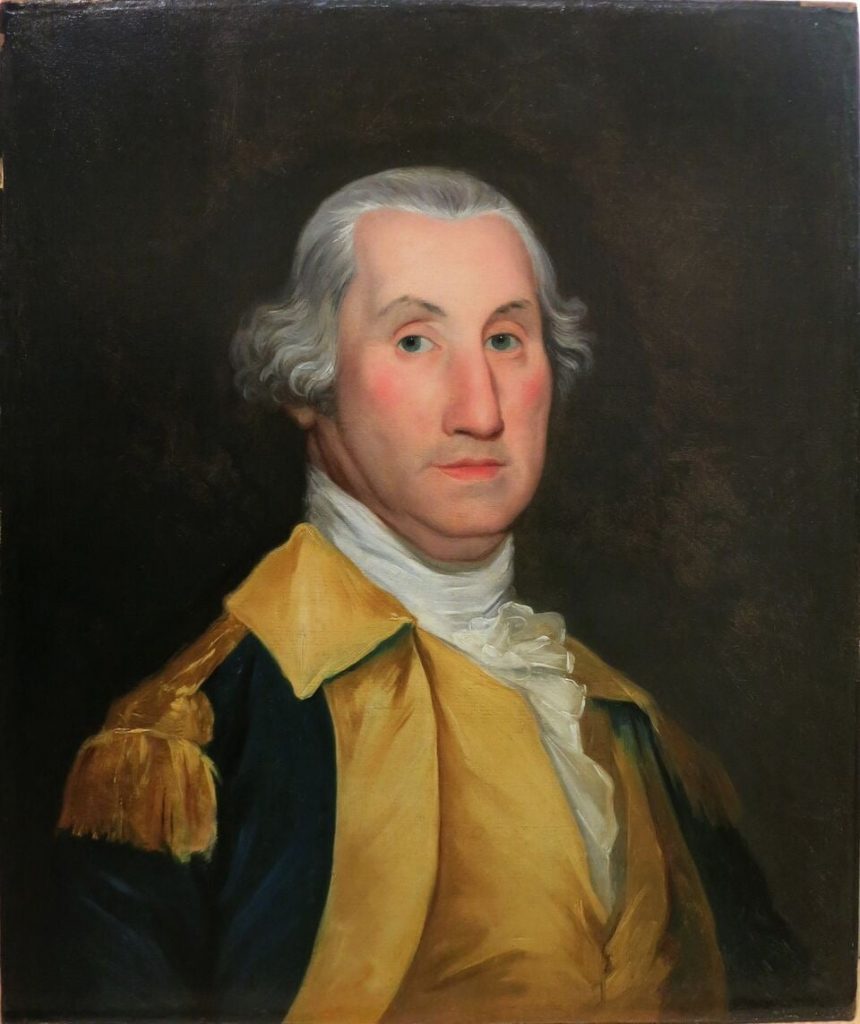

One of the first (and easiest) steps is to compare our portrait to other known images of Margaret Fuller. However, it is always important to consider the reliability of portraits as identification tools. Take the two portraits of George Washington pictured below, painted in the same decade by two established artists. If you look past the uniform and the signature hairstyle, you could be forgiven for thinking the portraits were of different people. The diversity of physical appearance evidenced within the large body of Washington portraits is a good reminder that a person’s appearance can vary based on their age at the time a likeness was taken, the medium of the likeness (for example, an oil portrait vs. a miniature), and the style or skill of the individual artist. Even when comparing known and suspected likenesses, it can be difficult to confirm an attribution in the absence of clear indicators like eye or hair color or well-documented facial features.

Washington as painted by Joseph Wright, 1783. Collection of Mount Vernon.

Portrait miniature of Washington painted by John Ramage, c.1789. Collection of The Met.

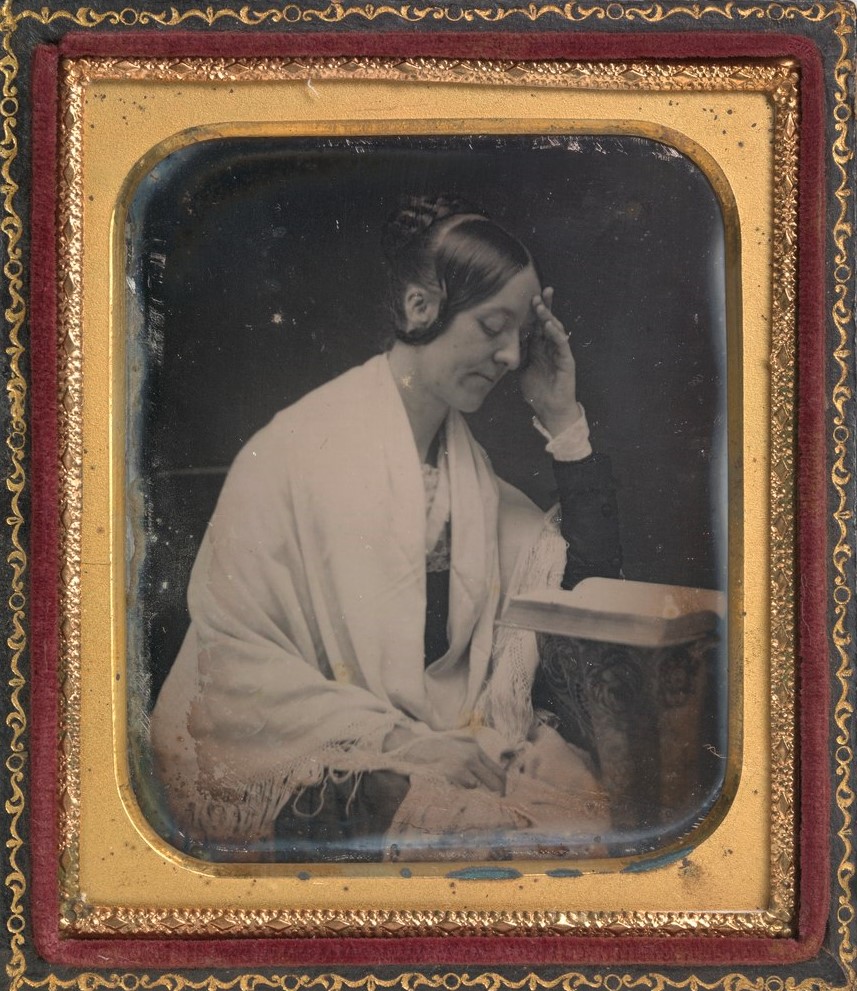

Fortunately, there are two extant likenesses of Fuller with strong documentation and provenance. One is a daguerreotype, or rather a grouping of near-exact daguerreotypes from the same session, taken by John Plumbe in New York in 1846. The second is a full-length oil portrait by American painter Thomas Hicks, whose stay in Italy likely overlapped with Fuller’s. The Hicks painting also inspired a later and widely-used engraving of Fuller.

Now, the bad news. While the two known likenesses of Fuller (pictured below) share certain characteristics, neither bears much resemblance to our supposed painting of her. Edgar Allen Poe described Fuller in Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1846 as having “a profusion of lustrous light hair,” eyes “a bluish gray, full of fire,” and “a capacious forehead.” One of Poe’s descriptors is of particular concern: having met Fuller on at least one occasion (see Weiss, The Home Life of Poe, 1907), he describes her as having “bluish gray” eyes, whereas the woman in our portrait has brown eyes. If Poe’s description of Fuller is accurate, it casts significant doubt on the sitter’s identity, as it is unlikely that a skilled portraitist would incorrectly record the color of Fuller’s eyes.

Daguerreotype of Margaret Fuller by

John Plumbe, 1846. Private collection.

Portrait of Margaret Fuller by Thomas Hicks, 1848.

Collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

There is one connection between Fuller and Litchfield, however, that could explain how a portrait of her would find its way into our collection. While working for Greeley, Fuller stayed with him and his wife, Mary Cheney, in their Manhattan home. Cheney was born in Litchfield, the daughter of prominent furniture maker Silas Cheney, and attended Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy from 1827 to 1829. She was also a likely alumna of Fuller’s Conversations.

Fuller’s friendship with the Cheney family seemingly continued after she left the Greeley’s home in 1846. The Historical Society’s collection includes a woman’s silk hat with a further connection to Margaret Fuller. According to object record, Fuller purchased the hat in Paris and sent it as a gift to a member of the Cheney family, whose relative later donated it to the Society. The parcel traveled to America ahead of Fuller, on the ship immediately preceding her own. If Fuller maintained a close enough relationship with the Cheneys to send gifts from her travels in Europe, it is not unthinkable that the family could own or later obtain a likeness of her. And while we have no record of who donated the portrait, it is also plausible that the donor was one of the Cheney descendants responsible for other gifts to the collection.

The case of the Society’s portrait of Margaret Fuller may never be definitively solved, but it demonstrates important lessons about museums and the objects they maintain, including the intricacies (and difficulties) of working with older collections, the importance of good object provenance (a term for the history of ownership), and the value of continued research.