Contributed by Bob Goodhouse

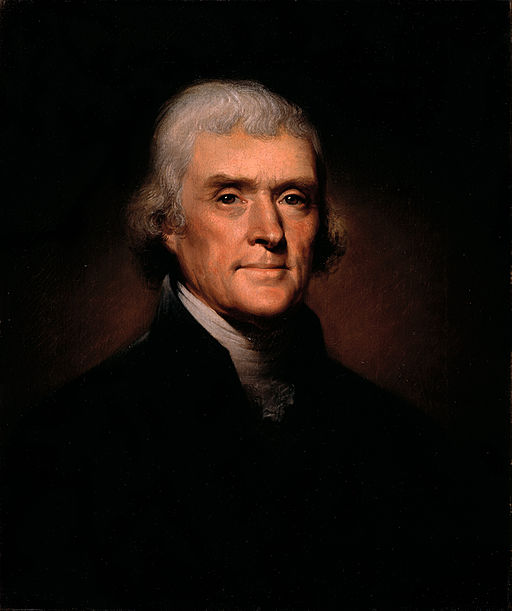

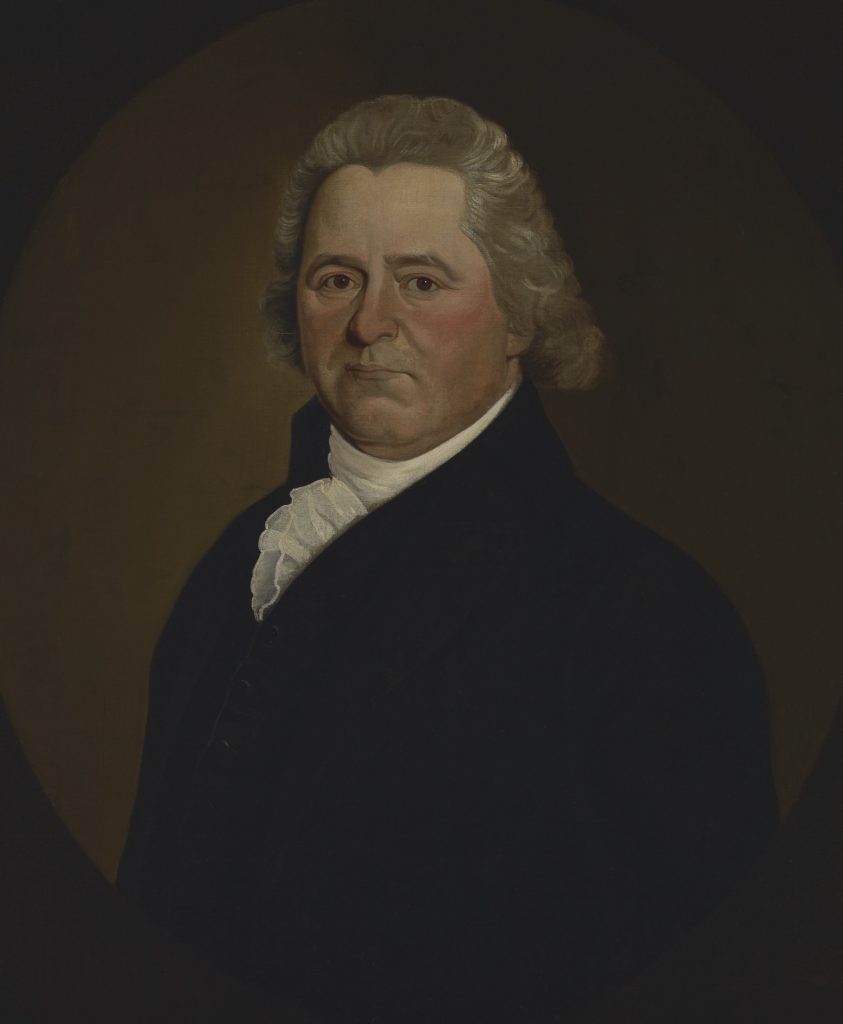

A grand jury indicted Tapping Reeve, founder of America’s first Law School and an esteemed Connecticut Superior Court Judge, for seditious libel against the United States and President Thomas Jefferson in the April 1806 New Haven Circuit Court.

The charge was based on an article Judge Reeve, an ardent Federalist, had sent to Litchfield’s The Monitor newspaper more than four years earlier, on December 2, 1801, in which Reeve had heatedly declared Jefferson’s violation of the U.S. Constitution, which he passionately insisted was now “marked for destruction.”

Reeve was one of the most respected and best-known legal minds in America and he had taught dozens of public office holders from several states. After the December 1801 article, he wrote over 25 more anonymous pieces in The Monitor from 1802-1803 condemning Jefferson and labelling Democratic-Republicans (“Republicans”) as “immoral, blaspheming sons of Sodom, boiling with lust, who were trying to destroy the Constitution and undermine the clergy”. He had a national audience, with his writings spread in Washington by his Congressional Federalist friends from Litchfield, Benjamin Tallmadge and Uriah Tracy, and his wide network of former students, both Federalists and Republicans, including John C. Calhoun and others.

Jefferson, President since 1800, had won a near-total electoral college re-election victory in 1804, and Connecticut and Delaware were the only states that he lost. With Connecticut as a bastion of the Federalist Party, the Republicans set their sights on weakening the Federalist hold on our state through, among other measures, control of Connecticut’s federal courts. To help achieve this goal, Jefferson appointed Pierpont Edwards, in February 1806, as District Court Judge, and Hezekiah Huntington, another Republican, as the new U.S. Attorney replacing Edwards.

Pierpont Edwards was the eleventh child of the famous Congregationalist theologian Jonathan Edwards. Edwards was also the uncle of Aaron Burr (and his sister Sally Burr, Mrs. Tapping Reeve), and was a Republican living in New Haven. One scholar suggests that Burr, while Vice President and before the controversy of his treason episode, had a window of time in 1805 when Jefferson felt he needed Burr’s support; this led to Jefferson agreeing to many of Burr’s suggested appointments, including making Edwards Connecticut’s District Court Judge, and a planned nominee to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Jefferson had made clear from the beginning of his Presidency in 1800 that he believed the Federalist hold on Connecticut was so strong that he would have to make appointments to federal offices of his Republican supporters. He wrote to Edwards in 1801: “… [I] declare the justice of some participation by the republicans in the management of public affairs, and the principles on which vacancies would be created.” (In the Reeve article of December 1801, opposition to “creating vacancies” in federal government positions through Jefferson’s decrees is a major topic.)

Then in 1803 Jefferson wrote to Thomas McKeon, Governor of Pennsylvania, regarding his frustration with the Federalist-controlled press: “… I have therefore long thought that a few prosecutions of the most prominent offenders would have a wholesome effect in restoring the integrity of the presses. Not a general prosecution, for that would look like persecution; but a selected one.”

By 1806 Jefferson had a strong party organization in Connecticut led by his state manager Alexander Wolcott of Middletown (a distant cousin of the Litchfield Wolcotts); the Federal Judge; the U.S. Attorney as well as the Federal Marshal, Joseph Willcox (who selected grand jurors).

U.S. Attorney Huntington got right to work after his appointment, issuing indictments in April 1806 session of the Court against three men: Judge Reeve for the 1801 article in The Monitor; Thomas Collier, The Monitor’s publisher; and Thaddeus Osgood, a divinity student who had preached a sermon criticizing Jefferson. In the next Court session of September 1806 he issued more indictments: to the publishers of the Federalist Connecticut Courant for accusing Jefferson of bribing Napoleon, and to a Bethlehem minister, Azel Backus, who had, during a sermon, called Jefferson “a liar, whoremaster, debaucher, drunkard, gambler,” and an infidel who appointed infidels to office.

The Grand Jury of April 1806, regarding Reeve and Collier, were instructed by Judge Edwards to consider that: “… a licentious press, regardless of decency or truth, under the conduct of daring men, stimulated by the spirit of revenge and unchecked in its career, will eventually destroy any government.”

The Jury dutifully returned indictments against Reeve, Collier and Osgood. Reeve and Collier posted sureties ($2,000 each) for their appearances in a trial; Osgood could not and was jailed.

As soon as the Grand Jury indicted Reeve, Judge Edwards began to have second thoughts. He decided to recuse himself from the case because he was Sally Burr Reeve’s uncle, and so had a kinship relationship with Reeve. But Mrs. Reeve had died in 1797, and Edwards’ recusal was not required by practice at that time. It is more likely that Edwards became aware of concerns among other Republican party members that he had gone too far with these indictments.

The leading Jeffersonian in Connecticut, Gideon Granger, Jefferson’s Postmaster General, thought the prosecution of Reeve, The Monitor, and the Connecticut Current, went against all Jeffersonian principles. Granger and others had vehemently protested the Adams Administration’s 1798 Sedition Acts, which resulted in U.S. Government lawsuits against several Federalist newspapers and now the Republican Administration was following the same approach. In October 1806 Granger wrote to Jefferson: “ Where will be the liberty of future generations if the dreadful doctrines maintained by Federalists on this point are to be sanctioned by precedents given by the republican administration?”

Specifically, the indictment of Reeve was causing Edwards embarrassment; Reeve was a beloved figure in many American political circles, both Federalist and Republican, having taught men from both parties. Closer to home, Edwards’ son and the Court’s Clerk Henry Waggaman Edwards (later the Governor of Connecticut) had studied under Judge Reeve at the Litchfield Law School.

At the April 1807 Court session, Edwards determined there were errors made by Huntington in drafting the indictments, and the cases against Reeve and Collier were postponed for a year. Huntington then told Edwards he was not prepared to prosecute Osgood, who was set free. And the September 1806 indictment of Reverend Backus was dredging up an old episode of Jefferson’s admitted seduction of a friend’s wife in 1768. Backus was planning to call as witnesses to his trial James Madison, General Henry “Light Horse” Lee, and the husband of the woman involved to use the affair to “prove” his comments in his sermon.

During that year-long delay Edwards assessed that most Republicans no longer had the political interest in pursuing the Reeve and Collier cases, especially in combination with the timing of the Backus case; and there was a backlash regarding the accusations against Reeve, despite the rhetoric in his anti-Jeffersonian writings.

Abruptly, in 1808, the cases against Reeve, Collier, and Backus were dismissed. In the case of Reeve, the records of the 1808 term of the Circuit Court state: “…and now Hezekiah Huntington, Attorney to said United States in the presence of the Court here maketh entry upon the said Indictment that he will no further prosecute the same. Therefore it is considered that the said indictment be dismissed.” Edwards then issued rulings which sent the Connecticut Courant case to the U.S. Supreme Court, where it was dismissed.

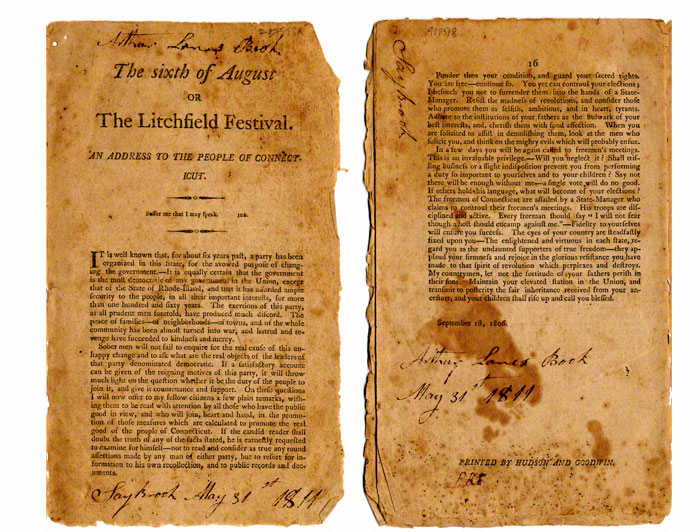

Tapping Reeve does not seem to have been concerned about the charges against him. He continued to write accusations of unconstitutional actions by the Republican Party and Jefferson himself, most notably in his pamphlet The sixth of August, or The Litchfield festival: an address to the people of Connecticut., published on September 1, 1806, four months after his indictment.

The Tapping Reeve indictment was politically driven, but it was rapidly viewed by most Republicans as an over-reaching mistake against a nationally revered figure. By encouraging the indictments, as shown in his instructions to the grand jury, Judge Edwards tried to show his Republican bona-fides to the Party and the Administration, with a goal of obtaining a Supreme Court seat in the future. When combined with the administrative errors made by the U.S. Attorney and the added prosecution of a stubborn Federalist preacher, Backus, who threatened to revive what had been a well-buried episode from Jefferson’s past, Edwards managed to end the episode without damage to his career. He never got a nomination to the Supreme Court, but he retained his Federal Judgeship until his death in 1826.

In the words of Law Professor Charles Heckman in the Connecticut Law Review of Spring 1996, “…no more hare-brained scheme could have been conceived than the prosecution of Tapping Reeve.”