By Bill Bucklin

Ephraim Kirby must have been a fascinating person to have a drink with during his service as a lawyer in Litchfield in the 1780s and 1790s.

Born in Woodbury, Kirby volunteered for Revolutionary War service just after the battle of Lexington and was wounded thirteen times. After the war he attended Yale University, leaving without a degree. After apprenticing to become a lawyer he was admitted to the bar and settled in Litchfield. Kirby’s son attended Tapping Reeve’s famous law school, where Reeve was teaching students to transpose English common law for the needs of America’s emerging legal system.

Kirby recognized the need for a written record of court decisions and began to compile any reports he could find. When the Connecticut legislature passed a law in 1785 requiring judges to prepare their decisions in writing, Kirby realized he had struck legal gold. Kirby spent three and a half years in a different form of service to his country, collecting every single Superior Court case report.

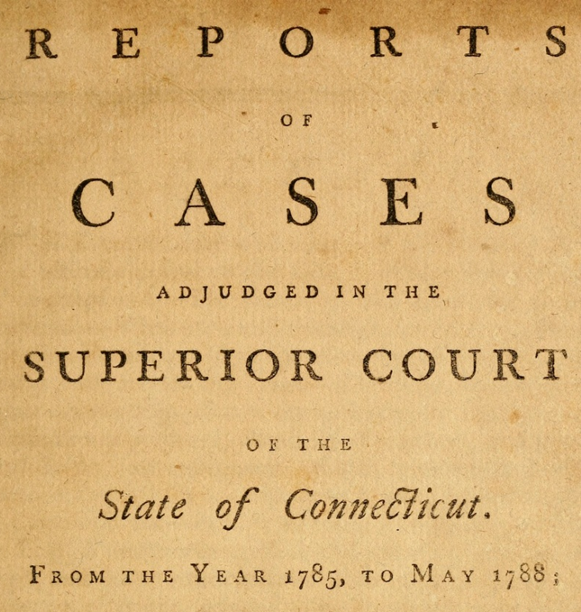

In 1789 Kirby visited Thomas Collier, Litchfield’s first printer, and left him with the manuscript of Reports of Cases Adjudged in the Superior Court of the State of Connecticut, from the year 1785, to May, 1788. Collier set the 425 pages of type, and in 1789 America’s first-ever volume of law reports was published.

Recognizing the volume’s significance, the Connecticut legislature ordered 350 copies which were sent to all Connecticut towns. It’s easy to imagine Tapping Reeve’s delight at adding this treasured volume to the Litchfield Law School’s expanding law library.