Contributed by Dan Keefe with Bob Goodhouse

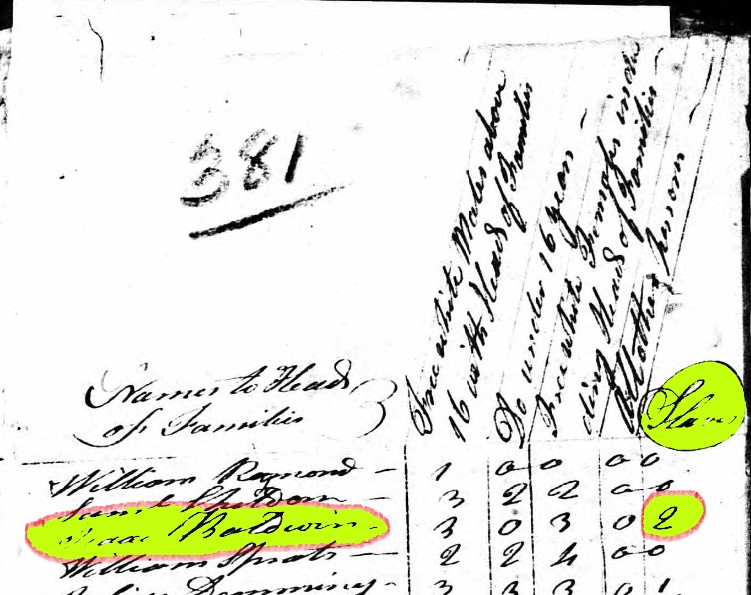

Twenty-six slaves are listed in Litchfield’s 1790 census including Sylvia Stocker, one of two people enslaved by Isaac Baldwin, Sr. Like all other slaves, she is recorded by number, not by name. In 1805, when Sylvia was 33, Baldwin’s heirs petitioned the Town Selectmen for her freedom and received their approval. Sylvia lived to be 64, and her will is recorded in Litchfield’s town records. Remarkably, she left her small library to the Town Selectmen for use by the poor.

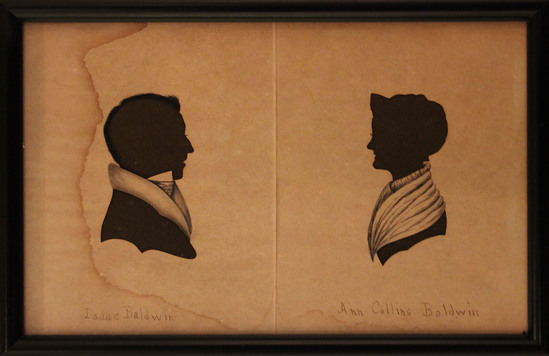

Isaac Baldwin, an early settler in Litchfield, married Anna Collins, daughter of Litchfield’s first minister, Timothy Collins. Baldwin held numerous leadership positions in Litchfield during his long life, becoming Town Clerk in 1742, a position he held for the next 31 years. His homestead stood in the complex formed by what we now know as the East Litchfield Road, Collins Road, Route 254, Fern Road and Route 118 .

Baldwin’s wife died at age 67, shortly before the 1790 Census was completed, and we can assume that Sylvia Stocker, at 18, became an essential caregiver for the aging widower. And it appears she married a free “Negro” sometime between 1790 and 1800.

The town records show:

- In the 1800 Federal Census the number of slaves fell from 26 in 1790 to 7 while the free black population of Litchfield is numbered at 58. Isaac Baldwin is not then recorded as one of the slave owners, but we know from further documents that Sylvia remained Baldwin’s “property.”

- The 1800 Census also lists a man named Orange Stocker, who is recorded in a column titled: ”Other” with a household of two, living near the Baldwin home.

- Litchfield Land Records in 1802 contain a record of Orange Stocker mortgaging his home for $100 to Horace Baldwin, a son of Isaac Sr. The deed reads:

“I Orange Stocker, a negro man of Litchfield…a certain dwelling house standing on the highway near the east line of the house lot of Isaac Baldwin, from the Litchfield Harwinton Turnpike… “

- When Sylvia was emancipated in 1805 she is named as “Sylvia Stocker.”

So the 1800 Census, the loan from Horace Baldwin to Orange Stocker, the location of the house as described in the loan, and the fact that Sylvia was later freed with the last name of Stocker, suggest that sometime between 1790 & 1800, while still enslaved, she was able to marry a free “Other” or ”Negro.”

By 1800, it is easy to imagine Isaac, the 85-year-old widower, as unable to remain in the homestead without the support of his slave, Sylvia, and with Orange Stocker, a free black hired hand. It is also easy to imagine Sylvia & Orange, with the Baldwin family’s approval, being allowed to set up a home close enough to Isaac’s dwelling to provide the care needed by the aging patriarch.

On Isaac’s death, January 15, 1805, aged 90 to 95, his heirs requested that Sylvia Stocker be emancipated.

Since slaves were property, emancipation had to be recorded in the Land Records. In addition, Selectmen needed to be assured that the slave wanted to be free, was capable of self-support, and that the person would not become the responsibility of the town instead of the heirs. The quotes below of the “transaction” are from the Litchfield Land Records at the Town Hall:

“Certify that we the subscribers, civil authorities and selectmen of the Town of Litchfield have enquired into the age, ability and health of Sylvia Stocker, a negro woman slave to Isaac Baldwin Esq. and find that she is 33 years old and no more and is in good health and that she wishes to be emancipated and we are of the opinion that it is proper that she be emancipated and hereby certify our willingness that said Isaac Baldwin Jr give to said Sylvia a letter of emancipation.

Dated 5/6/1805

Moses Seymour JP, Roger Whittlesey JP, Aaron Smith, Norman Buell, Noah Garnsey & Nathaniel Goodwin Selectmen

Sylvia’s Letter of Emancipation, From the heirs:

This is to certify that on behalf of myself and the other heirs of Isaac Baldwin, late of Litchfield, deceased, do hereby liberate and emancipate from slavery, Sylvia Stocker, a negro woman, late property of said deceased, Isaac Baldwin,

recorded September 6, 1806, Moses Seymour Register”

Sometime before 1812 Sylvia was widowed and sold the Stocker house to a Harry Fitch. Fitch, listed as an “Other” in Census records and as “Colored” in the records of St. Michael’s Church then moved the house to the area near the Bantam River, before the East Cemetery. It should be noted that many former enslaved and free black people lived in this area.

In 1815 Sylvia, together with a free black man named Pomp Lepeon, purchased a home located between Town Hill and Chestnut Hill on the corner of what today is Monfort Road. Sylvia owned 1/3 and Lepeon 2/3’s of the property.

On November 2, 1817, Sylvia remarried. St. Michael’s Church Records list the marriage of

Sylvia Stocking & Mose Grain(Green). That this is Sylvia Stocker is confirmed by the 1830 Census where she is recorded as Sylvia Green, a head of household and part of the East Street free black community that had grown to 26. That she is listed as “Head of Household” suggests that she was widowed for a second time.

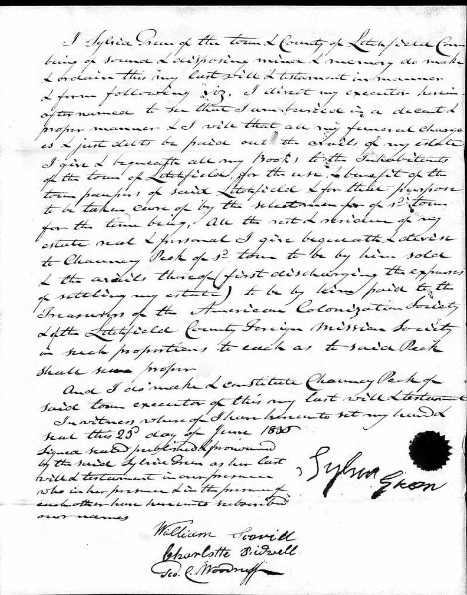

On June 23, 1836, three weeks before her death, Sylvia, then 64, responding to failing health, composed a will in which she leaves her small library for the Town Selectmen to share with the poor of Litchfield. So, this formerly enslaved woman created perhaps the first free Litchfield Lending Library, preceding the Wolcott Library founded in 1862 by 26 years and the Litchfield Circulating Library by 34 years.

Sylvia Stocker Green divided the rest of her small estate between The American Colonization Society, a group formed to support the colonization of free blacks in Africa, and the County Foreign Mission Society which sent missionaries to other lands for the purpose of bringing Christianity and conducting charitable & medical services.

Sylvia’s will is a unique piece of Litchfield History. Not only is it the only early 19th-century will of an African American in Litchfield found to date, but it holds echoes, if you listen closely, of her own enslavement, the struggles of newly freed Blacks, their fears and hopes and dreams. It speaks clearly of her concern for a people scarred by slavery, sharing with us her sense that, because she could, she must share her small estate with others less fortunate.

This post was created by Dan Keefe with Bob Goodhouse.